Generative Adversarial Networks

credit: most content in this post is a summary of the paper Generative Adversarial Networks, published at NeurIPS 2014, by Ian Goodfellow and colleagues at the Unviersity of Montreal.

The paper introduces a new generative model composed of two models trained simultaneously:

- a generative model G that captures the data distribution; and

- a discriminative model D that estimates the probability that a sample came from the training data rather than G;

The training procedure for G is to maximize the probability of D making a mistake. This framework is the minimax 2-player game. The adversarial framework comes from the fact that the generative model faces the discriminative model, that learns wether a sample is from the model distribution or from the data distribution. Quoting the authors: “The generative model can be thought of as analogous to a team of counterfeiters, trying to produce fake currency and use it without detection, while the discriminative model is analogous to the police, trying to detect the counterfeit currency. Competition in this game drives both teams to improve their methods until the counterfeits are indistiguishable from the genuine articles.”

Mathematical setup

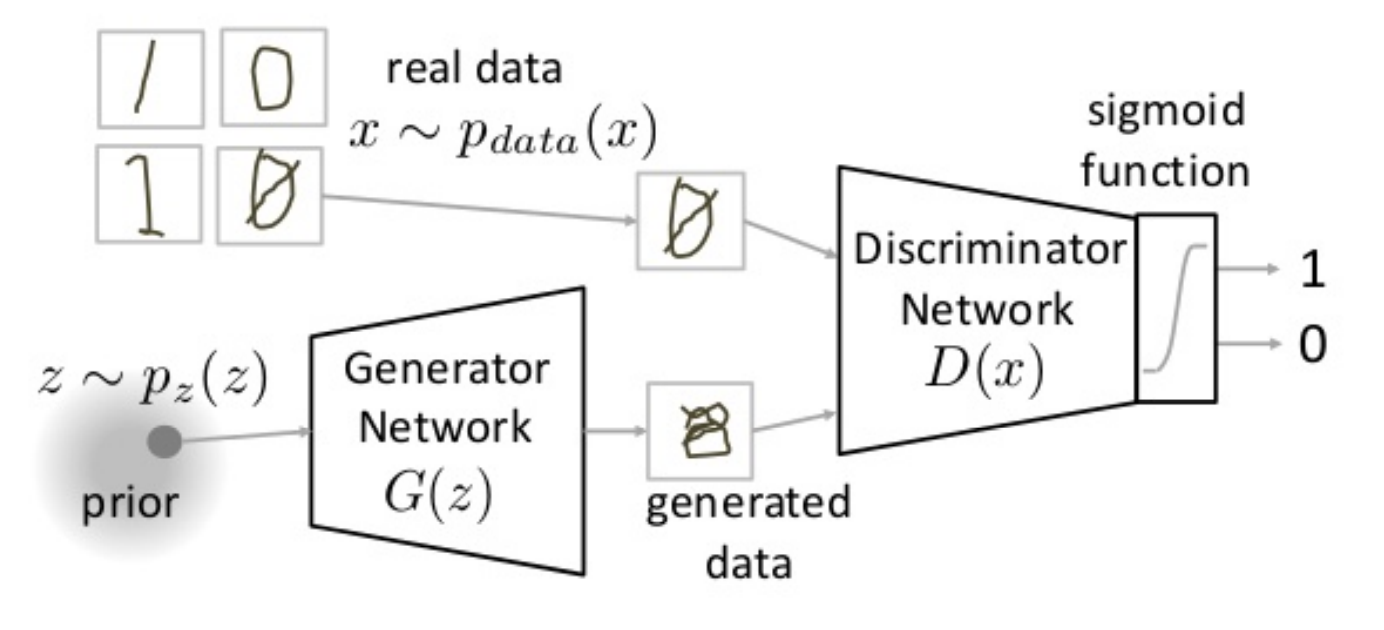

The goal of the generative model is to generate samples by passing a random noise \(z\) through a multilayer perceptron.

- The generator \(G(z \mid \theta_g)\) is a multilayer perceptron with parameters \(\theta_g\).

- \(p_z(z)\) is the prior on the input noise variables.

- The generator \(G\) implicitly defines a probability distribution \(p_g\) as the distribution of the samples \(G(z)\) obtained when \(z \sim p_z\);

- The goal of the generator is to learn the distribution \(p_g\) over data \(x\), in order to fake it “well enough” and trick the discriminator;

The discriminative model is also a multilayer perceptron.

- The discriminator \(D(x \mid \theta_d)\) takes the input \(x\) and based on its DNN parameters \(\theta_d\) it outputs a single scalar representing the probability that \(x\) came from the data rather than \(p_g\);

The overall structure of the generator and discriminator training can be pictured as:

The GAN model (image credit: Benjamin Striner, lecture notes CMU 11-785)

Loss and minimax challenge

We train the discriminator \(D\) to best guess the source of the data, i.e. maximize the probability to assign the correct label to the training example and samples from \(G\).

We train the generator \(G\) simultaneously to minimize \(1-D((G(z)))\), i.e. be able to fake the data well enough. In practice, \(D\) and \(G\) are playing a two-player minimax game with value function \(V(G,D)\):

The loss function is a sum of two penalization terms:

- on the first term we optimise the discriminator, such that on the long run, we expect all real inputs (drawn from the data, ie \(x \sim p_{data}\)) to be as correct as possible;

- on the second term we optimise the discriminator and discriminator, such that on the long run, we expect all fake inputs (generated by the discriminator, ie \(z \sim p_z\)) to be also as correct as possible;

Finally, notice there is a \(log\) term added to both expected value terms. This is because the objective function is the product of multiple probabilities, in this case \(D(x) * (1-D(G(z)))\). Adding the \(log\) makes the optimisation return the same optima — as \(log\) is monotonic — while making it faster and more numerical stable. We also add the expectation term to the loss because we want to minimize the loss that we expect after several samples (law of large numbers). Thus:

\[\mathbb{E} \left[ log(D(x) * (1-D(G(z)))) \right] = \mathbb{E} \left[ log(D(x)) \right] + \mathbb{E} \left[ log(1-D(G(z))) \right]\]In section 4 (theoretical results) the authors show that indeed, when given enough capacity to the discriminator and generator, it is possible to retrieve the data generating distribution. In practice, it shows that this minimax game has a global optimum for \(p_g = p_{data}\), and therefore the loss function can be optimized.

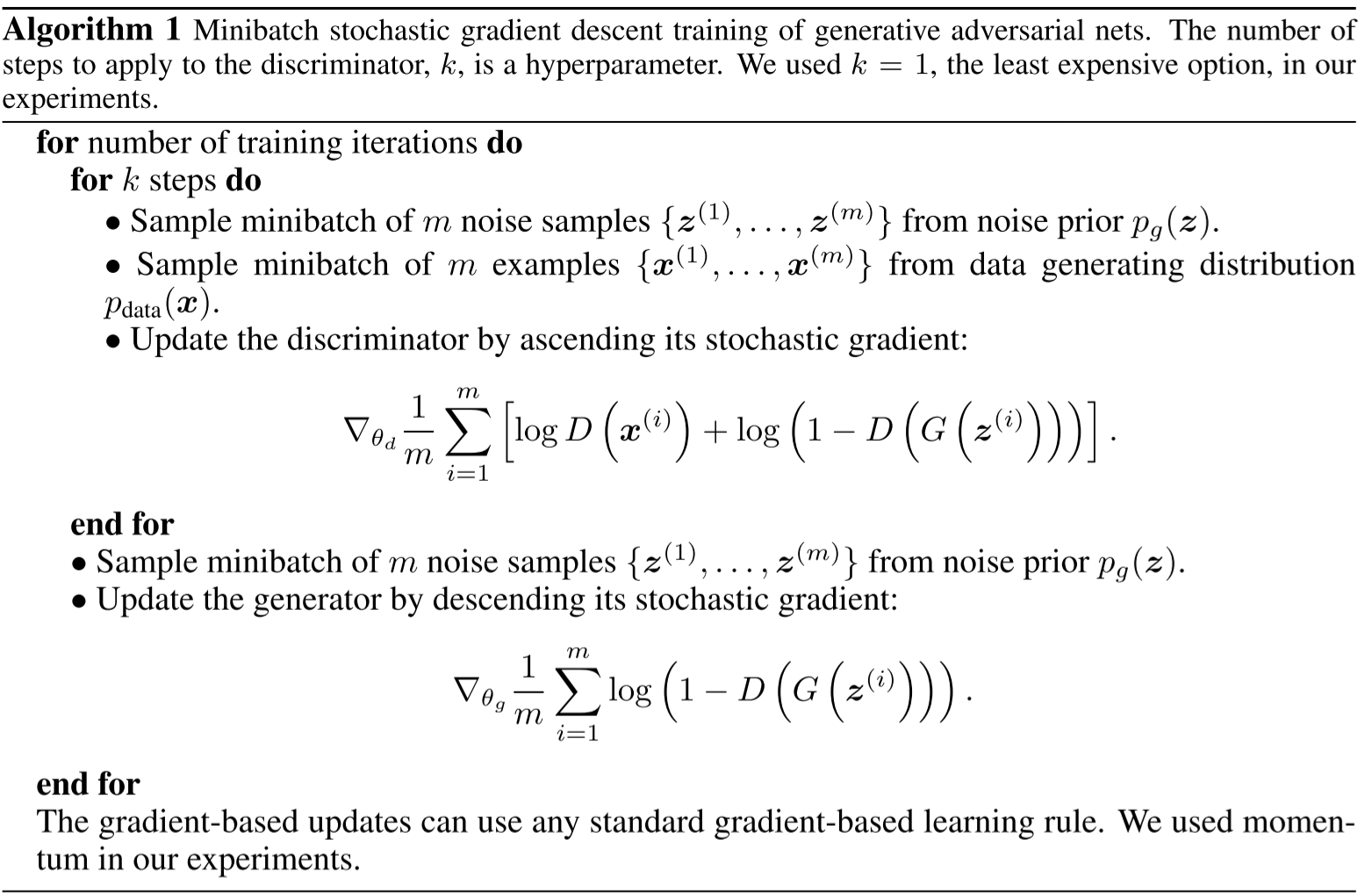

Challenge: different convergence speed in the optimization of Generator and Discriminator

Because the objective function is much simpler, the discriminator trains much faster than the discriminator. To overcome it, training is performed by alternating between \(k\) steps of optimizing \(D\) and one step of optimizing \(G\). The underlying rationale is that “early in learning, when \(G\) is poor, \(D\) can reject samples with high confidence because they are clearly different from the training data. In this case, \(log(1 − D(G(z)))\) saturates.

Challenge: saturation of discriminator loss

The loss equation may not provide sufficient gradient for \(G\) to learn well. Early in learning, when \(G\) is poor, \(D\) can reject samples with high confidence because they are clearly different from the training data. In this case, \(log(1 − D(G(z)))\) saturates. Saturation means it’s not updating . Which means it is on some kind of a local minimum rather than in the desired global minima. In practice this means that this term of the loss function will not provide any signal (gradients) for the update of the loss, making it useless. I.e. when the discriminator performs significantly better than the generator, the updates to the discriminator are either inaccurate, or disappear.

This leads to two main problems:

- mathematically, the update of the parameters is none or very small, so the stepping in the loss landscape is very slow;

- computationally, arithmetic operations over very small values lead to incorrect (or “always zero”) results due to insufficient floating point precision in the processor (typically 16 or 32 bits);

The work around suggested by the authors is to change the algorithm for training the generator, and instead of minimizing \(\log(1 − D(G(z)))\), they maximize \(\log D(G(z))\) so that the optimisation landscape “provides much stronger gradients early in training”. See the pseudocode at the end of this post for a clearer explanation.

Challenge: Mode collapse

This challenge was not part of the original publication, and it was not discovered until later. In a regular scenario, we want GANs to generate a range of outputs, or ideally, a new random valid output for every random input to the generator. Instead, it may happen that sometimes we have a monotonous output, i.e. a range of very similar outputs. This phenomenon is called Mode Collapse and is detailled in this paper as: “This event occurs when the model can only fit a few modes of the data distribution, while ignoring the majority of them”. In this article they propose a workaround using second-order gradient information. However, this is a field of intense research and several solutions have been proposed, to name a few: a different loss function (Wasserstein loss), Unrolled GANs that incorporates current and future discriminator’s classification in the loss function (so that generator can’t over optimize for a single discriminator), Conditional GANs, VQ-VAEs, etc…

Training algorithm

This final training algorithm is the following: