Variational Autoencoders

credit: most content in this post is a summary of the papers Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes and An Introduction to Variational Autoencoders from Diederik P. Kingma, Max Welling at the Uversiteit van Amsterdam.

The papers introduces Variational Autoencoders, aiming at performing efficient inference and learning in probabilistic models whose latent variables and parameters have intractable posterior distributions, and on large datasets. The SGVB (Stochastic Gradient Variational Bayes) estimator presented can be used for efficient approximation of posterior inference in almost any model with continuous latent variables, and because it’s differentiable, it can be optimized with e.g. gradient descent. The AutoEncoding Variational Bayes (AEVB) algorithm presented uses the SGVB estimator to optimize a model that does efficient approximate posterior inference using simple sampling (from parametric distributions).

The VAE is a probabilistic auto-encoder, where the probabilistic encoder (aka recognition model) and decoder (aka generative model) are represented as neural networks. The AEVB algorithm is a learning/inference algorithm that can be used to find the parameters of the VAE, i.e. to perform approximate variational inference in the directed graphical model of the VAE.

Input datapoints \(x\) are generated as following:

- a value \(z(i)\) is generated from some prior distribution \(p_{\theta^*}(z)\); and

- a value \(x(i)\) is generated from the likelihood distribution \(p_{\theta^∗}(x \mid z)\).

The assumptions are that both the prior and likelihood functions are parametric differentiable distributions, and that \(\theta^*\) and \(z(i)\) are unknown. There’s also the assumption of intractability as in:

- the integral of the evidence or marginal likelihood \(\int p_\theta(z) p\theta(x \mid z) dz\) is intractable;

- the true posterior density \(p\theta (z \mid x)\) is intractable, so the expectation maximization algorithm cant be used; and

- the algorithms for any mean-field approximation algorithm are also intractable. This is the level of intractability common to DNNs with nonlinear hidden layers.

The paper propose solutions to an efficient approximation of MAP estimation of parameters \(\theta\), of the posterior inference of the latent variable \(z\) and the marginal inference of the variable \(x\). Similarly to other variational inference methods, the intractable true posterior \(p_{\theta}(z \mid x)\) is approximated by \(q_\phi(z \mid x)\) (the Encoder), whose parameters \(\phi\) are not computed by a closed-form expectation but by the Encoder DNN instead. \(p_\theta(x \mid z)\) is the Decoder, that given a \(z\) will produce/generate the output which is a distribution over the possible values of x. Given a datapoint \(x\) the encoder produces produces a distribution (e.g. a Gaussian) over the possible values of the code \(z\) from which the datapoint \(x\) could have been generated.

Non-Variational vs Variational AutoEncoders

The VAE proposed includes a DNN decoder, a DNN decoder, with parameters \(\theta\) and \(\phi\) optimized together with the AEVB algorithm, where \(p_\theta(x \mid z)\) is a Gaussian/Bernoulli with distribution parameters computed from \(z\). Therefore the VAE can be viewed as two coupled, independent parameterized models: the encoder/recognition models, and the decoder/generative model (trained together), where the encoder delivers to the decoder an approximation to its posterior over latente random variables.

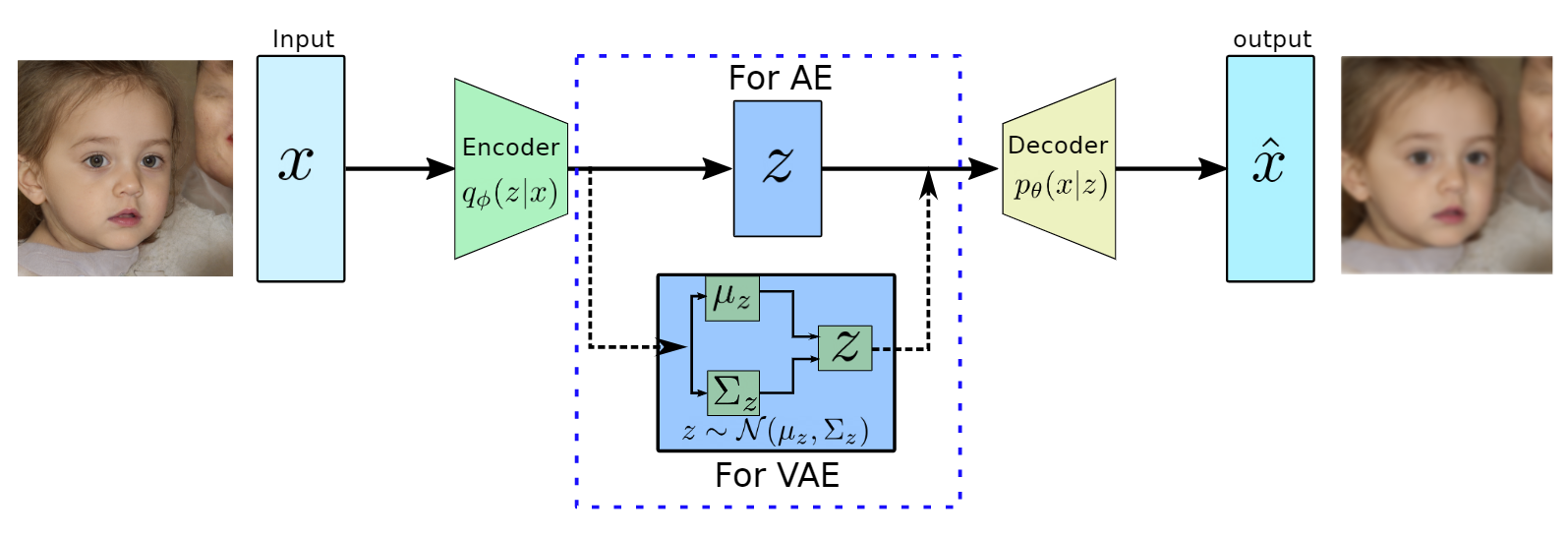

The difference between Variational Autoencoders and regular Autoencoders (such as sequence-to-sequence encoder-decoder) is that:

- in regular AEs the latent representation of \(z\) is both the output of the encoder and input of the decoder;

- in VAEs the output of the decoder are the parameters of the distributions of \(z\) – e.g. mean and variance in case of a Gaussian distribution – and \(z\) is drawn from those parameters and then passed to the decoder;

In practice, they can be vizualised as:

VAE vs AE structure (image credit: Variational Autoencoders, Data Science Blog, by Sunil Yadav))

Why VAE instead of Variational Inference

One advantage of the VAE framework, relative to ordinary Variational Inference, is that the encoder is now a stochastic function of the input variables, in contrast to VI where each data-case has a separate variational distribution, which is inefficient for large datasets.

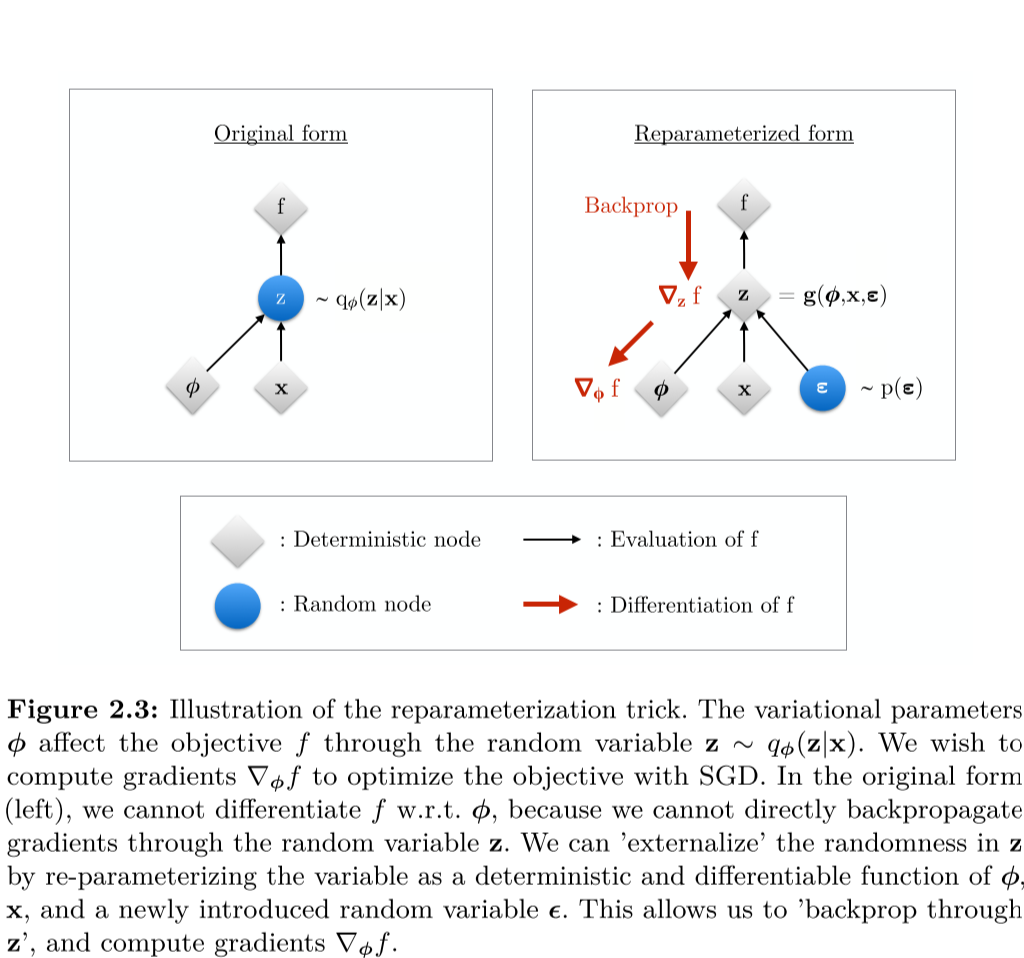

The reparametrization Trick

The authors noticed that the sampling induces sampling noise in the gradients required for learning (or that because \(z\) is randomly generated and cannot be backpropagated), and to counteract that variance they use the “reparameterization trick”.

It goes as follows: the sample vector \(z\) that is typically sampled from the mean vector \(\mu\) and the variance \(\sigma^2\) in the Gaussian scenario in now described as \(z = \mu + \sigma \cdot \epsilon\) where \(\epsilon\) is the standard gaussian ie \(\epsilon \sim N(0,1)\).

The loss function

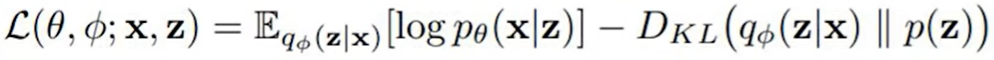

The loss function is a sum of two terms:

The first term is the reconstruction loss (or expected negative log-likelihood of the i-th datapoint). The expectation is taken with respect to the encoder’s distribution over the representations, encouraging the VAE to generate valid datapoints. This loss compares the model output with the model input and can be the losses we used in regular autoencoders, such as L2 loss, cross-entropy, etc.

The second term is the Kullback-Leibler divergence between the encoder’s distribution \(q_{\theta}(z \mid x)\) and the standard Gaussians \(p(z)\), where \(p(z)=\mathcal{N}(\mu=0, \sigma^2=1)\). This divergence compares the latent vector with a zero mean, unit variance Gaussian distribution, and penalizes the VAE if it starts to produce latent vectors that are not from the desired distribution. If the encoder outputs representations \(z\) that are different than those from a standard normal distribution, it will receive a penalty in the loss. This regularizer term means ‘keep the representations \(z\) of each digit sufficiently diverse’.

Results

The paper tested the VAE on the MNIST and Frey Face datasets and compared the variational lower bound and estimated marginal likelihood, demonstrating improved results over the wake-sleep algorithm.

Detour: why do we maximize the Expected Value?

In the Bayesian setup, it is common that the loss function is the sum of the expected values of several terms. Why?

It all goes down to the Law of large numbers. According to the law, the average of the outcomes of a large number of trials should be close to the expected value, and it tends to approximates the expected value as the number of trials increases.

Imagine we are playing a game (BlackJack, Slots, Rock-Paper-Scissors) that is repeatable as many times as desired. Because of the law of large numbers, we know that value of wins will over \(n\) iterations of the game will approximate \(n \mathbb{E}(X)\). In practice, we want to optimise our problem according to the most-likely outcome of our experiment, i.e. maximize its expected value;

So in practice, the law of large numbers will often guarantee a better outcome over the long run, and we maximize that outcome by maximizing the expected outcome of our optimisation in the long run.