Publications bookmark

A summary of some interesting publications I came across. Continuously updated. Click \(\small{\blacktriangleright}\) to expand.

2025 SLA: Beyond Sparsity in Diffusion Transformers via Fine-Tunable Sparse-Linear Attention

SLA targets the attention bottleneck in Diffusion Transformers (DiTs), where long generation chains make per-step latency especially costly. Instead of committing to a single approximation (pure sparsity or pure linear attention), the paper proposes a hybrid view of attention weights: some interactions are critical and must remain “exact-ish,” while many are marginal or negligible and can be approximated or dropped.

The method combines sparse attention (for the important interactions) with a linear component (to cheaply capture the broad, low-impact mass), and introduces a fine-tunable mechanism that can adapt which interactions belong to which bucket. This makes SLA behave like a “knob” between dense and approximate attention: you can dial sparsity/linearity while preserving fidelity, which helps differentiate it from static sparse masks or fixed-kernel linear attention.

In their evaluation, SLA reports large compute reductions and practical wall-clock speedups: up to 95% attention computation reduction and up to 20× attention speedup in some settings, and 13.7× attention speedup plus 2.2× end-to-end video generation speedup on Wan2.1-1.3B.

2025 DeepSeek‑V3.2‑Exp (model card & notes), DeepSeek‑AI

DeepSeek‑V3.2‑Exp is an incremental update in the DeepSeek V3 family aimed primarily at serving efficiency, especially for long-context workloads. Compared to the original DeepSeek‑V3 technical report (Dec 2024), the emphasis shifts from “how we trained it” to “how we run it cheaper”: the release focuses on lowering attention/memory costs and improving throughput without changing the core MoE transformer recipe.

The headline change is DeepSeek Sparse Attention (DSA): instead of dense attention over all tokens, the model uses a sparse scheme that combines a lightweight “indexer” with fine-grained token selection so attention is concentrated on the most relevant tokens/blocks. In effect, this trades a bit of extra bookkeeping for fewer key/value interactions at long sequence lengths, targeting better prefill efficiency and lower KV-cache pressure.

The Hugging Face release notes also call out practical serving details (recommended runtime settings, known issues/fixes, and evaluation notes). If you already have DeepSeek‑V3 deployed, treat V3.2‑Exp as a serving-oriented refresh: expect the biggest wins when context lengths are large, while short-context quality/behavior should remain close to V3.

2025 DeepCompile: A Compiler-Driven Approach to Optimizing Distributed Deep Learning Training, Microsoft DeepSpeed

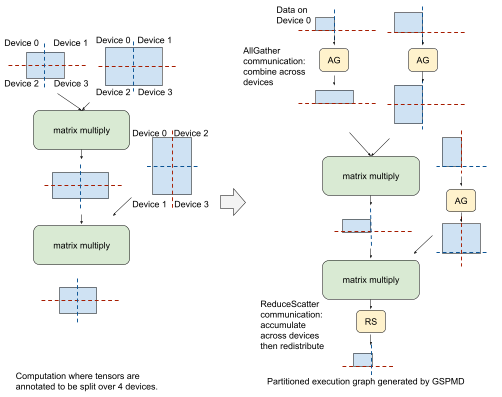

DeepCompile extends the capabilities of deep learning compilers to support distributed training. “Distributed training has become essential for scaling today’s massive deep learning models. While deep learning compilers like PyTorch compiler dramatically improved single-GPU training performance through optimizations like kernel fusion and operator scheduling, they fall short when it comes to distributed workloads.”

Existing distributed training frameworks require distributed optimizations to be implemented at the PyTorch level, which limits the ability to apply compiler-style techniques like dependency analysis or operator scheduling. “The fully sharded approach, as implemented in systems like ZeRO-3 and FSDP, employs runtime optimizations such as prefetching and unsharding:

- Prefetching aims to reduce communication overhead by initiating all-gather operations earlier than the layer where the parameters are actually needed, thereby overlapping communication with computation;

- unsharding keeps parameters in their full form to reduce communication when memory permits;

DeepCompile addresses this gap by enabling compiler-level optimizations for distributed training. It takes a standard single-GPU model implementation and transforms it into an optimized multi-GPU training graph without requiring changes to the model code”. DeepCompile applies a fully sharded approach like ZeRO-3 and FSDP on top of DeepCompile, along with three optimizations: proactive prefetching, selective unsharding, and adaptive offloading.

- Proactive prefetching. To maximize overlap between communication and computation, this optimization pass initiates all-gather as early as possible, considering how available memory changes as the forward and backward passes progresses.

- Selective unsharding. This pass keeps as many parameters unsharded as possible to reduce communication overhead caused by all-gather communication, and decides which parameters to unshard based on operator-level memory profiling

- Adaptive offloading. DeepCompile offloads optimizer states such as momentum and variance used by Adam [14] to CPU memory when GPU memory is insufficient. To reduce data transfer overhead, it offloads only the amount of data that exceeds the memory limit and schedules transfers to overlap with computation.

It automatically implements distributed ZeRO-3, ZeRO-1, and offloading. Future directions include automated parallelization (sequence/tensor parallelisms), smarter memory management, and dynamic adaptation to runtime behavior.

2025 Triton-distributed: Programming Overlapping Kernels on Distributed AI Systems with the Triton Compiler

Triton-distributed extends Triton with distributed primitives so you can write kernels that compute and communicate inside the same program, rather than launching a GEMM kernel and then calling NCCL as a separate step. The paper’s mental model is “a distributed kernel is a set of asynchronous tasks” that can signal one another and use symmetric memory (NVSHMEM-style) to move data directly between GPUs.

The key difference vs “plain Triton + NCCL” is that communication becomes an explicit part of the kernel schedule: the compiler/runtime can overlap loads, math, and remote puts/gets at a much finer granularity than stream-level overlap of independent kernels. Compared to systems like Flux/TileLink that focus on specific LLM communication patterns, Triton-distributed tries to be a general programming model (primitives + compiler support) that you can reuse across operators and topologies.

Results / takeaways:

- The paper reports speedups ranging from ~1.1× to ~20.7× on a set of distributed workloads (with the larger gains typically coming from communication-heavy patterns where fine-grained overlap matters).

- It also reports ~1.3× to ~2.4× speedups on distributed MoE workloads by enabling fused compute–communication kernels rather than staging communication into separate NCCL phases.

- In practice, it’s a “make the compiler responsible for overlap” approach: you write a single kernel that contains both compute and the collective-ish data movement, and the system handles the async orchestration.

2025 TileLink: Generating Efficient Compute–Communication Overlapping Kernels Using Tile-Centric Primitives

TileLink is a step toward Flux-like performance without requiring you to hand-craft a very specialized fused kernel for each operation. It introduces a tile-centric abstraction: tensors are mapped into 2D tiles, and the system schedules computation and communication per tile (rather than per whole tensor), enabling overlap that approximates what highly tuned systems achieve.

A useful way to distinguish TileLink from nearby work:

- Flux: decomposes specific tensor-parallel LLM ops into finely sliced pieces, then fuses them into larger kernels to overlap up to “almost all” communication; highly effective, but quite tailored.

- Triton-distributed: offers low-level in-kernel primitives (symmetric memory, signals, tasks) and a general programming model.

- TileLink: sits in between—higher-level than Triton-distributed, more general and easier to program than Flux, but still explicitly models overlap at the tile schedule level.

Results / takeaways:

- The paper reports ~1.17× to ~20.76× speedups compared to a baseline that uses standard PyTorch + NCCL-style communication patterns, depending on the operator and communication intensity.

- Against Flux specifically, TileLink reports ~1.09× to ~1.14× speedups on the workloads evaluated, positioning itself as competitive with (and sometimes slightly better than) a strong hand-optimized baseline—while aiming for broader applicability and simpler programming.

2025 MegaScale-MoE: Large-Scale Communication-Efficient Training of Mixture-of-Experts Models in Production

MegaScale-MoE is a production-oriented system for communication-efficient MoE training, where the “hard part” is not just computing experts but routing tokens and moving activations/gradients at scale. The paper’s central point is that MoE training becomes dominated by many-to-many communication (e.g., all-to-all between token routers and experts), and that you need a holistic strategy (parallelism + communication scheduling + careful micro-batching) to keep GPUs busy.

How it differs from “kernel-level fusion” work (Flux / TileLink / Triton-distributed):

- MegaScale-MoE is primarily a system/runtime + parallelization strategy for end-to-end training at very large scale, not a new kernel programming model.

- It focuses on how to structure MoE training (expert placement, token routing, communication patterns, pipeline/micro-batch choices) so the cluster behaves well, even if the underlying collectives are still “standard”.

Results / takeaways (as reported):

- The paper reports up to ~2.0× end-to-end training speedup on 32K H800 GPUs, trained on ~5 trillion tokens, for a ~7.5B-parameter model.

- The headline is that communication efficiency is not a rounding error at this scale; the system-level choices can plausibly double effective throughput in real production settings.

2025 MegaScale-Infer: Serving Mixture-of-Experts at Scale with Disaggregated Expert Parallelism

MegaScale-Infer targets MoE serving, where routing + expert execution creates sharp bottlenecks (many-to-many traffic, load imbalance, and memory-bound expert kernels). The key architectural idea is disaggregated expert parallelism: separate attention and expert “sides” so the system can schedule and pipeline them differently, and use a purpose-built communication substrate for the expert routing path.

Compared to training-focused MoE systems (including MegaScale-MoE), this paper is more about:

- Latency/throughput in inference (including scheduling under request load),

- Ping-pong / pipelined execution between attention and expert nodes,

- A custom many-to-many communication library and memory-bound kernel optimizations.

Results / takeaways (as reported):

- For a 220B MoE model on 1024 A100 GPUs, the paper reports ~2.6× to ~4.3× speedup over baseline systems.

- For a 3T MoE model on 2048 H800 GPUs, it reports ~2.9× to ~5.4× speedup.

- For online serving scenarios, it reports ~1.6× (220B / 1024 A100) and ~2.5× (3T / 2048 H800) improvements, emphasizing that the scheduling/communication choices help under realistic request patterns, not just offline throughput.

2025 Accelerating MoE Model Inference with Expert Sharding

Balmau et al. study MoE inference from a perspective that’s easy to underestimate: even if your attention path is well optimized, expert execution and routing can dominate in sparse MoE models, and naive expert placement can create large communication volume and poor load balance.

Their approach, “expert sharding,” explores splitting experts across GPUs in a way that:

- Improves memory capacity and where expert weights live,

- Trades off communication vs. replication of weights,

- Exposes when Megatron-style GEMM parallelism helps (and when it just moves the bottleneck into communication).

This work is a useful complement to MegaScale-* systems: it is more about exposing and characterizing the performance envelope of sharded experts (and showing what makes it hard), whereas MegaScale focuses on a full production stack.

Results / takeaways: the paper’s main value is the systems analysis and the evaluation of sharding strategies that highlight which communication patterns remain dominant and where more aggressive fusion/overlap could help.

2025 Look Ma, No Bubbles! Designing a Low-Latency Megakernel for Llama-1B

This work targets an extreme low-latency regime: single-sequence decoding for a ~1B-parameter LLM, where performance is dominated by how efficiently the GPU can stream weights from global memory. The authors argue that modern inference engines still suffer from “pipeline bubbles” because a forward pass is split into dozens to ~100 small kernels, each incurring launch/teardown costs and synchronization stalls that prevent continuous memory streaming.

Their solution is to fuse the entire forward pass into a single megakernel that effectively acts like an on-GPU interpreter: each SM executes a schedule of “instructions” (fused RMSNorm+QKV+RoPE, attention, projections, MLP pieces, etc.). They then focus on three practical problems that show up when you fuse “about a hundred” operations:

- How to program such a megakernel (an instruction abstraction + interpreter),

- How to avoid resource contention (e.g., paged shared memory to pipeline weight loads),

- How to synchronize without kernel boundaries (a lightweight counter-based scheme).

Results / takeaways (as reported):

- On an H100, they report using ~78% of available memory bandwidth and outperforming popular engines by >1.5×; they also report that vLLM and SGLang can be limited to around ~50% bandwidth in this setting.

- In their end-to-end comparison (32-token prompt, 128 generated tokens, no speculation), they report the megakernel is ~2.5× faster than vLLM and >1.5× faster than SGLang on H100.

- On B200, they report >3.5× speedup over vLLM and still >1.5× over SGLang.

- They highlight achieving a <1 ms forward pass for a 16-bit 1B+ model on H100, and <680 µs per forward pass on B200.

This sits in a different part of the design space than Flux/TileLink/Triton-distributed: it’s about eliminating kernel boundaries entirely for single-GPU low-latency inference, rather than fusing compute with distributed communication.

2025 Mirage: A {Multi-Level} Superoptimizer for Tensor Programs (OSDI 2025)

Mirage is an automatic approach to generating deeply fused tensor programs, framing kernel fusion as a superoptimization problem over “µGraphs” (small fused subgraphs that can resemble hand-designed kernels like FlashAttention). The key point is automation: rather than manually designing a megakernel or a fused attention kernel, Mirage searches a large space of fused implementations and applies multi-level transformations to find fast code.

How it differs from other “big fusion” lines:

- Compared to manual megakernels (e.g., “No Bubbles”), Mirage aims to discover aggressive fusions automatically and generate optimized implementations.

- Compared to FlashAttention-style work, Mirage is broader: it targets arbitrary tensor programs (not just attention), and can potentially find FlashAttention-like structures when they are profitable.

- Compared to compiler frameworks like TVM/XLA, Mirage emphasizes superoptimization over small fused graphs to get performance that can beat hand tuning.

Results / takeaways (as reported in the paper):

- Mirage reports speedups of ~1.03× to ~4.6× on the forward pass across evaluated workloads and baselines.

- For end-to-end training, it reports ~1.04× to ~1.14× improvements over strong, tuned baselines—smaller than the biggest kernel-level wins, but meaningful given how optimized many training stacks already are.

2025 SageAttention3: Microscaling FP8 Attention for Inference

SageAttention3 pushes the SageAttention line toward even more aggressive inference acceleration by combining microscaling FP8 with attention-specific numerical tricks, aiming to keep attention accurate while driving GPU throughput. Conceptually, it sits between “attention kernels that assume FP16/BF16” and “end-to-end quantized models”: it focuses on the attention operator itself and is designed to be dropped into existing inference stacks.

On RTX 5090, the paper reports that SageAttention3 can reach up to 7.4× the OPS of FlashAttention3 (fp16) and up to 3.3× the OPS of FlashAttention3 (fp8), while maintaining high accuracy.

2024 SageAttention2: Efficient Attention with Thorough Outlier Smoothing and Per-thread INT4 Quantization

SageAttention2 builds on SageAttention by moving to INT4 quantization for the expensive (QK^\top) path (at a thread-level granularity) while using FP8 for the \,(\widetilde{P}V)\, product. The key idea is that attention has quantization pathologies that don’t show up as strongly in linear layers—especially outliers—so the paper adds attention-specific techniques to make low-bit arithmetic viable.

Concretely, it proposes (1) per-thread INT4 quantization for (Q,K), (2) a smoothing method for (Q) to improve INT4 (QK^\top) accuracy, and (3) a two-level accumulation strategy to improve FP8 (\widetilde{P}V) accuracy. The paper reports that on RTX 4090, SageAttention2’s OPS surpasses FlashAttention2 and xFormers by about 3× and 4.5×, respectively, and that it can match FlashAttention3(fp8) speed on Hopper while achieving higher accuracy.

2024 SageAttention: Accurate 8-Bit Attention for Plug-and-play Inference Acceleration

SageAttention is an “attention-first” quantization paper: rather than quantizing an entire model, it targets the attention kernel and aims to make it plug-and-play for existing LLM inference. The motivation is that, even when linear layers are heavily optimized, attention can remain a major bottleneck—especially at long sequence lengths—because it mixes GEMMs, softmax, and reductions in ways that amplify numerical outliers.

The core idea is to run attention with 8-bit arithmetic while preserving accuracy via attention-aware scaling/handling of outliers (the paper emphasizes that naïvely quantizing (QK^\top) tends to break). Compared to later SageAttention2/3, this first version is less aggressive (INT8-style rather than INT4/FP8 microscaling) and functions as the baseline that demonstrates the feasibility of attention quantization with minimal integration work.

For performance, the paper reports substantial throughput gains on consumer GPUs: on RTX 4090, SageAttention achieves up to 8.4× higher OPS than FlashAttention2 (and up to 11.5× over xFormers), and peaks at 983 TOPS (head dim 128).

2024 Centauri: Enabling Efficient Scheduling for Communication–Computation Overlap in Large Model Training via Communication Partitioning

Centauri tackles communication–computation overlap at the operator scheduling level. The core idea is to decompose operators and then schedule the decomposed pieces across multiple CUDA streams so that communication can be overlapped with useful compute more consistently than “whole-operator overlap.” The “communication partitioning” framing highlights that a large collective (or data movement phase) can be broken into smaller chunks that are scheduled earlier and more frequently, improving pipeline utilization.

How to situate Centauri relative to Flux / TileLink / Triton-distributed:

- Centauri is mainly about multi-stream scheduling of decomposed operators and improving overlap among (still separate) kernels; it does not require in-kernel collectives.

- Flux/TileLink/Triton-distributed pursue in-kernel fusion of compute and communication, which can overlap at a finer granularity, but often requires more specialized codegen/primitives.

- Centauri is therefore a good fit when your bottleneck is orchestration (stream scheduling, dependencies, coarse kernel granularity), whereas Flux-like approaches target cases where overheads persist even with aggressive stream overlap.

Results / takeaways: the paper reports substantial training speedups on Llama-scale workloads by improving overlap through decomposition + scheduling. (If you end up writing your own fused kernels later, Centauri is still useful as a baseline: it shows what you can get “for free” from better scheduling alone.)

2024 FLUX: Fast Software-based Communication Overlap on GPUs Through Kernel Fusion

Flux is explicitly designed around Megatron-LM-style tensor-parallel patterns. Instead of treating tensor-parallel layers as “one big GEMM + one big NCCL collective,” Flux decomposes those operations into fine-grained pieces (e.g., tiles/chunks) and then fuses them into kernels that can overlap communication with computation aggressively—claiming overlap levels that are hard to reach with standard multi-stream overlap of separate kernels.

The most useful way to think about Flux in the related-work landscape:

- Compared to Centauri, Flux aims for overlap within the operator, not just between independent kernels.

- Compared to Triton-distributed, Flux is less about a general programming model and more about delivering peak performance for a specific family of LLM ops (Megatron tensor-parallel attention/MLP patterns).

- TileLink is motivated partly by Flux’s effectiveness: it tries to preserve Flux-like performance while raising the programming level.

Results / takeaways (as reported):

- Flux reports up to ~96% communication overlap.

- For Megatron-LM Llama-style inference, it reports up to ~1.66× speedup for prefill and ~1.3× for decoding.

- For training, Flux reports ~1.2× to ~1.5× speedups for Llama-3 8B pretraining, evaluated on 8-node and 3–5 node clusters with 8 GPUs per node (e.g., 24–64 GPUs total).

2024 Optimizing Distributed ML Communication with Fused Computation–Collective Operations

Punniyamurthy et al. focus on identifying common “compute + collective” motifs that appear repeatedly in distributed training/inference graphs and then implementing them as single fused kernels with in-kernel collectives. The contribution is partly a taxonomy (“these patterns show up everywhere”) and partly a concrete engineering result: implementing fused kernels in Triton/HIP that reduce overheads from intermediate writes, kernel boundaries, and separated communication steps.

The paper’s patterns are especially useful to keep in mind when comparing systems:

- Flux is very focused on tensor-parallel LLM patterns; this paper’s catalog is broader (e.g., embedding + all-to-all, GEMV + all-reduce, GEMM + all-to-all).

- Triton-distributed/TileLink offer programming models to build such fused kernels; this paper provides hand-built instances and measurements that show why the fusion matters.

- Unlike INC/offload approaches, these fused kernels still assume the communication happens through GPU-side primitives (no in-network execution).

Results / takeaways (as reported):

- The paper reports latency reductions of about 29% for embedding + all-to-all, 26% for GEMV + all-reduce, and 35% for GEMM + all-to-all, showing that the win can be material even for “simple” two-stage pipelines when communication is tightly coupled to the compute.

2024 DeepSeek-V3 Technical Report

DeepSeek-V3 is a large-scale LLM system report that’s useful to read as a “what it takes in practice” reference: model architecture decisions, training stack choices, and the kinds of engineering trade-offs that are often omitted from purely algorithmic papers. The details are particularly relevant in a related-work section that discusses communication-heavy structures (like MoE) and the real limits of standard communication substrates.

Where it fits in the landscape here:

- DeepSeek-V3 demonstrates that you can hit strong scaling and quality with careful MoE architecture/routing and training practices, but it largely relies on standard collectives/communication stacks rather than pushing compute–communication fusion into the kernels or the network.

- This makes it a good “control point” when discussing what incremental improvements from fused kernels or in-network compute might buy: you can compare against a strong end-to-end system that already works at scale.

Results / takeaways: the report is a systems-and-training reference more than a single “one trick” optimization; it’s most valuable for its end-to-end design and empirical scaling observations, which help ground discussions about where communication becomes dominant and what kinds of optimizations remain on the table.

2024 The Llama 3 Herd of Models, Meta

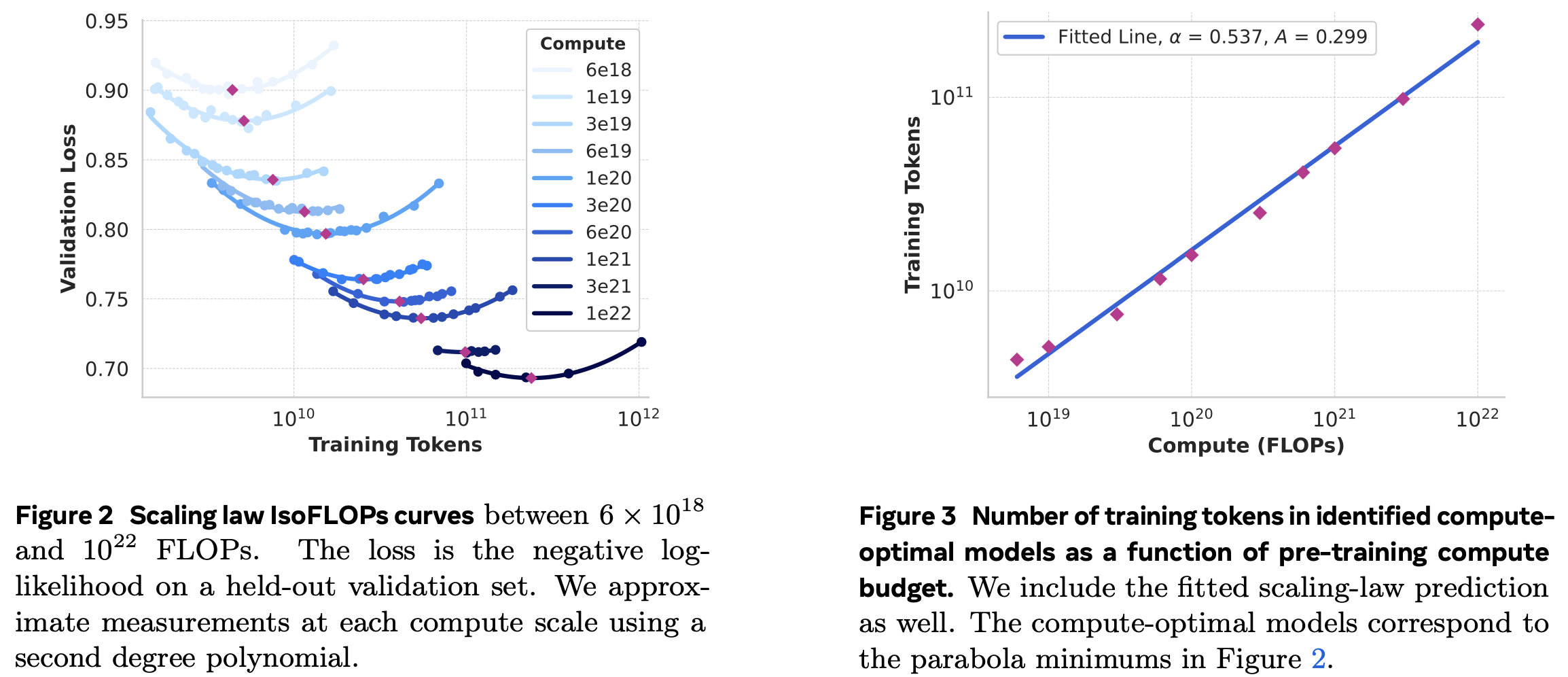

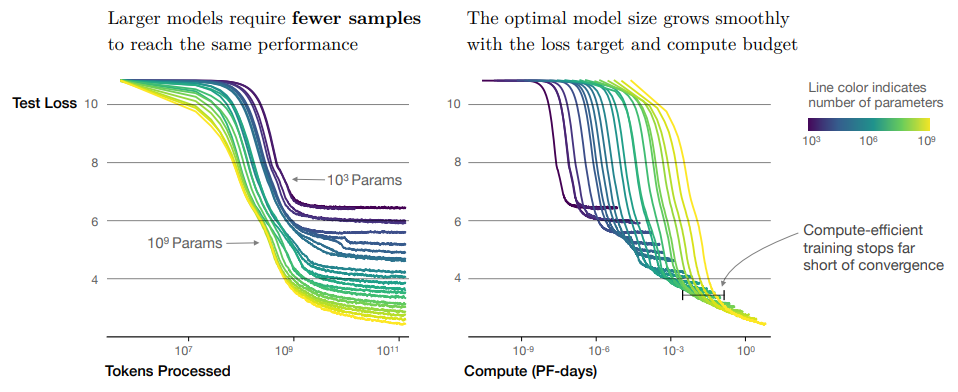

Llama 3 is “a herd of language models that natively support multi-linguality, coding, reasoning, and tool usage.” The models are made of 8B, 70B and 405B parameters and a context window of 128K tokens. Llama 3 405B uses an architecture with 126 layers, a token representation dimension of 16,384, and 128 attention heads. Llama 3 405B is trained on up to 16K H100 GPUs, via 4D parallelism (tensor, pipeline, context and data). The authors used scaling laws (Hoffmann et al., 2022;) to determine the optimal model size for our flagship model given our pre-training compute budget (section 3.2.1), where they establish a sigmoidal relation between the log-likelihood (figure 4):

The model architecture does not deviate from Llama 2, except that they:

- use grouped query attention with 8 key-value heads to improve inference speed and to reduce the size of key-value caches during decoding, and

- “use an attention mask that prevents self-attention between different documents within the same sequence as is important in continued pre-training on very long sequences”.

- vocabulary with 128K tokens: 100K from

tiktokenand 28k for better non-English support. - increase the RoPE base frequency hyperparameter to 500,000 to better support longer contexts.

Training is performed in two stages: pre-training via next-token prediction or captioning, and post-training where the model is “tuned to follow instructions, align with human preferences, and improve specific capabilities (for example, coding and reasoning).” The improvements were performed at 3 levels:

- at the data level, the authors improved quality, quantity, pre-processing and curation. The dataset includes “15T multilingual tokens, compared to 1.8T tokens for Llama 2.”

- At the scale level, the model increased its size almost \(50 \times\), reaching now \(3.8 \times 10^{25}\) FLOPS; and

- managing complexity, where they used a regular transformer with minor adaptations instead of a mixture of experts, and “a relatively simple post-training procedure based on supervised finetuning (SFT), rejection sampling (RS), and direct preference optimization (DPO), as opposed to more complex reinforcement learning algorithms.” (section 4)

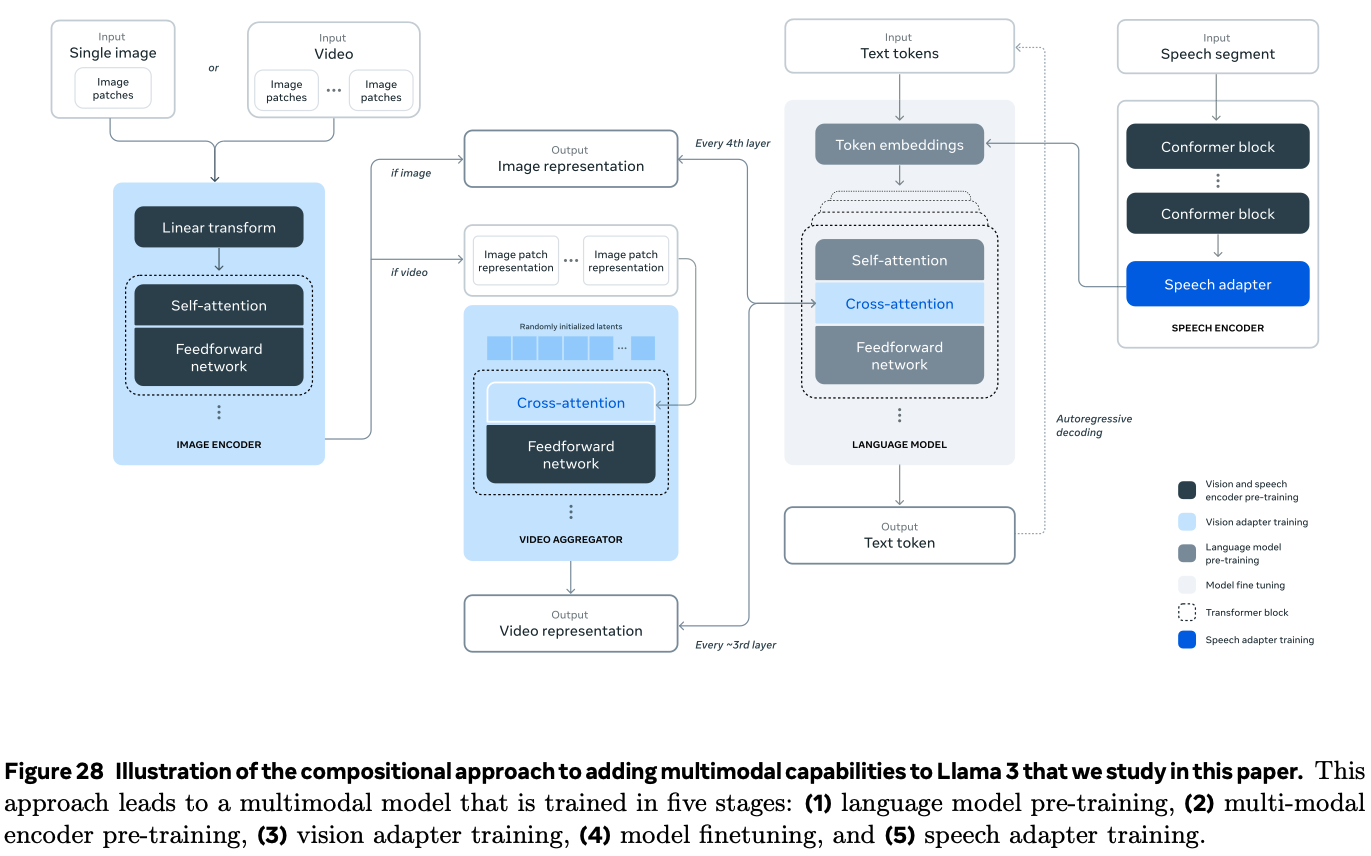

The authors also experiment adding image, video, and speech capabilities, by adding three additional stages:

- multi-modal encoder pre-training, where train and speech encoders are trained separately (sections 7 and 8). The image encoder is trained large amounts of image-text pairs, using self-supervised learning that “masks out parts of the speech inputs and tries to reconstruct the masked out parts via a discrete-token representation”.

- vision-adapter training, where the authors train an adapter on text-image pairs to align image representations with language representations. Then they train a video adapter on top of the image adapter on paired video-text data, to enable model to aggregate information across frames (section 7).

- Speech adapter training: a third adapter converts speech encodings into token representations.

The image encoder is a standard vision transformer trained to align images and text, the ViT-H/14 variant. They introduce cross-attention layers (Generalized Query Attention) between the visual token representations produced by the image encoder and the token representations produced by the language model, at every 4th layer.

Results (section 5) investigate the “performance of: (1) the pre-trained language model, (2) the post-trained language model, and (3) the safety characteristics of Llama 3”.

In section 6, they investigated two main techniques to make inference with the Llama 3 405B model efficient: (1) pipeline parallelism on 16 H100s with BF16 and (2) FP8 quantization. FP8 quantization is applied to most parameters and activations in feed-forward network but not to parameters of self-attention layers of the model. Similarly to Xiao et al 2024b they use dynamic scaling factors for better accuracy (with upper bound of 1200), and do not perform quantization in the first and last Transformer layers, and use row-wise quantization, computing scaling factors across rows for parameter and activation matrices.

2024 Universal Checkpointing: Efficient and Flexible Checkpointing for Large Scale Distributed Training, Microsoft DeepSpeed

According to the paper, the issue with state-of-the-art distributed checkpointing (model save/resume) is that it requires “static allocation of GPU resources at the beginning of training and lacks the capability to resume training with a different parallelism strategy and hardware configuration” and usually it is not possible to resume when hardware changes during the training process. To this extent, the paper proposes “Universal Checkpointing, a technique that enables efficient checkpoint creation while providing the flexibility of resuming on arbitrary parallelism strategy” and “ improved resilience to hardware failures through continued training on remaining healthy hardware, and reduced training time through opportunistic exploitation of elastic capacity”. This is achieved by writing in the universal checkpoint format, which allows “mapping parameter fragments into training ranks of arbitrary model-parallelism configuration”, and universal checkpoint language that allows for “converting distributed checkpoints into the universal checkpoint format”. The UCP file is a gathering of all distributed saves into a single file per variable type (optimizer state, parameters, etc).

2024 Domino: Eliminating Communication in LLM Training via Generic Tensor Slicing and Overlapping, Microsoft DeepSpeed

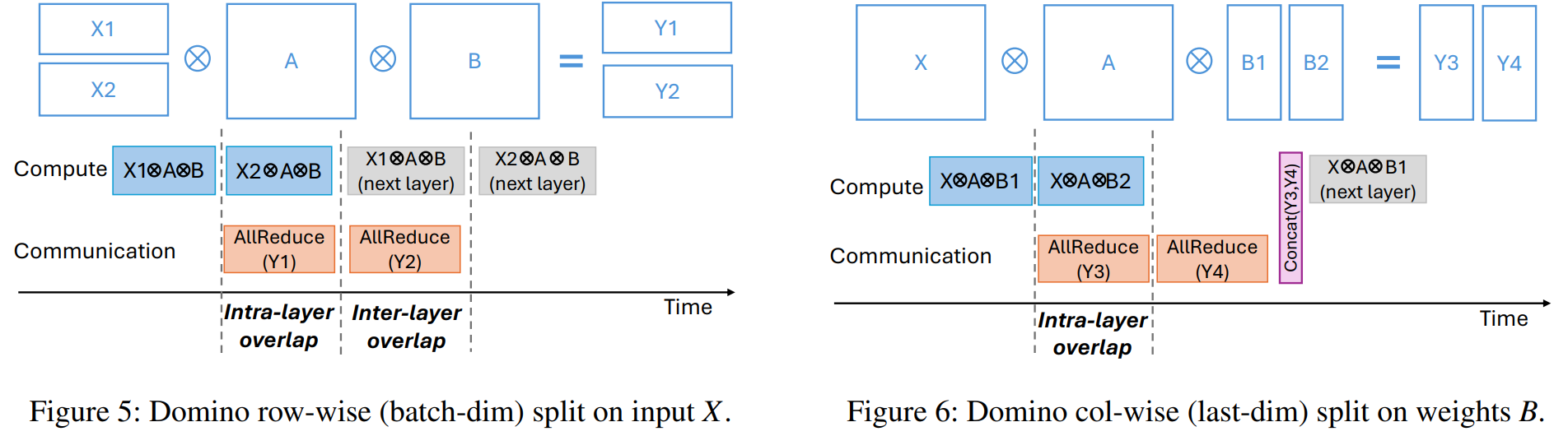

Domino “provides a generic scheme to hide communication behind computation” when training large LLMs where tensor parallelism (TP) is applied. “By breaking data dependency of a single batch training into smaller independent pieces, Domino pipelines these independent pieces training and provides generic strategy of fine-grained communication and computation overlapping. … comparing with Megatron-LM, Domino achieves up to 1.3x speedup for LLM training on Nvidia DGX-H100 GPUs”. The rationale for the paper is: current efforts to overlap computation and communication during TP are not enough, especially “in the cases where collective communication takes much longer than a single GeMM computation, most of the communication time still stands out as the major training overhead”. And “given that computation on the latest GPUs is becoming faster, communication overhead is more pronounced”. The paper proposes “Domino, a generic approach that breaks data dependency of transformer model training into pieces, and then pipelines these pieces training to overlap communication with computation …. Domino provides a much wider scope of computation and communication overlapping (e.g., AllReduce not only overlaps with a single GeMM, but also LayerNorm, DropOut, etc). … To hide TP communication behind computation, Domino provides extra and generic tensor partition in two dimensions on every GPU: row-wise split on inputs X and column-wise split on weights B on top of original TP model partitions. At high level, Domino generically breaks TP’s \(X \cdot A \cdot B\) into smaller compute units without data dependency. Then it pipelines these independent compute units with collective communication to achieve fine-grained computation and communication overlapping … we keep \(A\) untouched and do not conduct any tensor partitioning on \(A\). Therefore, we only conduct tensor slicing on input tensor \(X\) (section 3.2) and the second group of linear weights as \(B\) (section 3.3). We also provide a hybrid tensor partition strategy of both \(X\) and \(B\) (section 3.4). After these tensor slicing, Domino breaks \(X \cdot A \cdot B\) into pieces and removes data dependency. Then we enable computation-communication overlapping on these independent pieces to reduce communication overhead in TP.”

2023 Simplifying Transformer Blocks, ETH Zurich

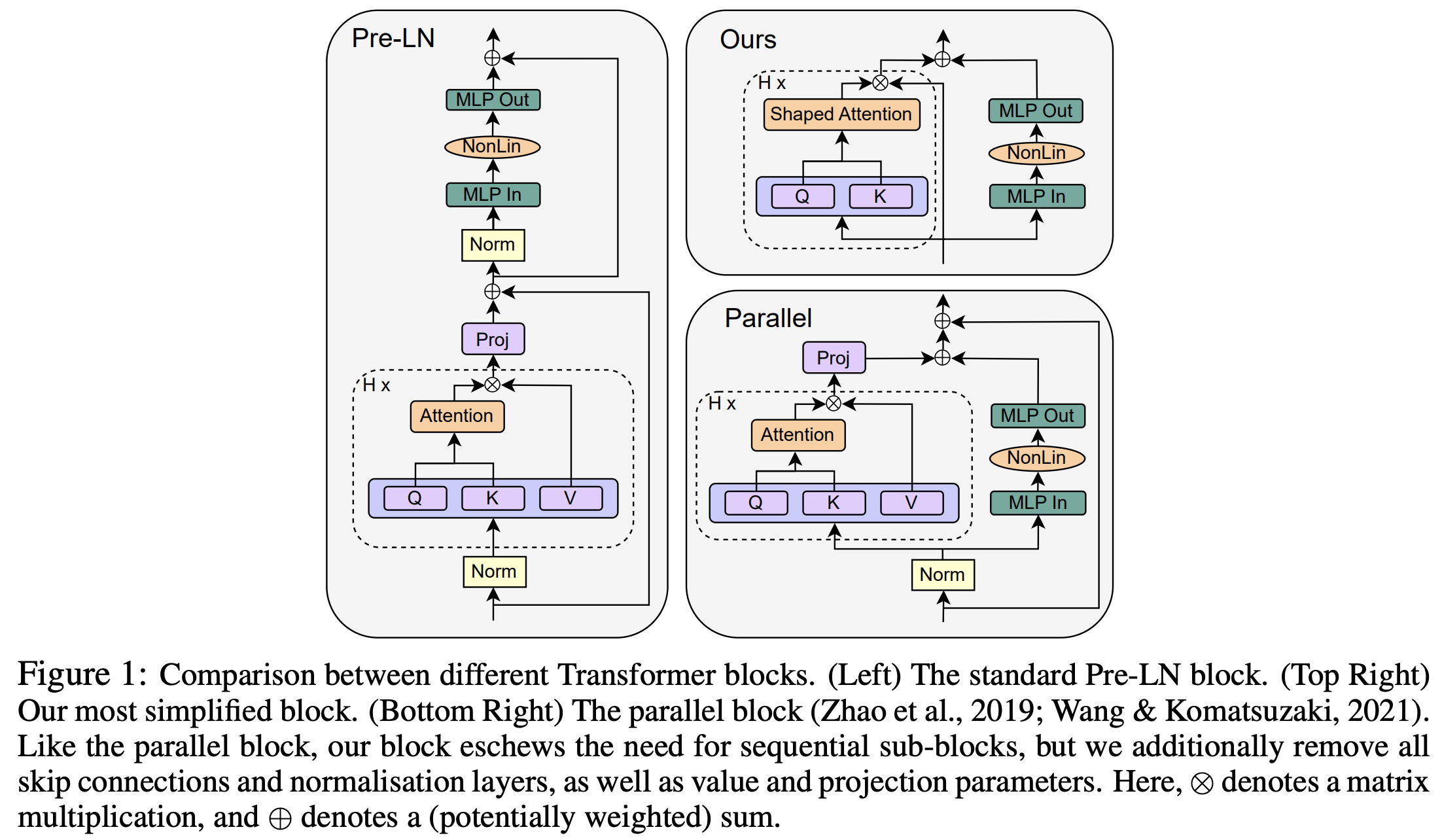

A simpler transformer architecture that claims similar results to state-of-the-art autoregressive decoder-only and BERT encoder-only models, with a 16% faster training throughput, while using 15% fewer parameters.

2024 The Road Less Scheduled, Meta

“Existing learning rate schedules that do not require specification of the optimization stopping step T are greatly out-performed by learning rate schedules that depend on T.” The Schedule-Free approach is an optimization method that does not need the specification of T by removing the need of schedulers entirely. It requires no new hyper-parameters.

Backgroung: take the typical SGD optimization with step size \(γ\) in the form \(z_{t+1} = z_t − γ_{g_t}\), where \(g\) is the gradient at step \(t\). “Classical convergence theory suggests that the expected loss of this \(z\) sequence is suboptimal, and that the Polyak-Ruppert (PR) average \(x\) of the sequence should be returned instead” as \(x_{t+1} = (1 − c_{t+1}) x_t + c_{t+1} z_{t+1}\). If we use \(c_{t+1} = 1/(t+1)\), then \(x_t = \frac{1}{T} \sum_{t=1}^T z_t\). As an example, after 4 steps we have:

\[\begin{align*} x_1 = & z_1\\ x_2 = & \frac{1}{2} x_1 + \frac{1}{2} z_2, \\ x_3 = & \frac{2}{3} x_2 + \frac{1}{3} z_3, \\ x_4 = & \frac{3}{4} x_3 + \frac{1}{4} z_4, \\ x_5 = & \frac{4}{5} x_4 + \frac{1}{5} z_5, \\ \end{align*}\]However, “despite their theoretical optimality, PR averages give much worse results in practice than using the last-iterate of SGD”:

Recently, Zamani and Glineur (2023) and Defazio et al. (2023) showed that the exact worst-case optimal rates can be achieved via carefully chosen learning rate schedules alone, without the use of averaging. However, LR schedulers requise the definition of the stopping time T in advance. So the question of the paper is:

Do there exist iterate averaging approaches that match the empirical performance of learning rate schedules, without sacrificing theoretical guarantees?

This paper shows that it exists by introducing “a new approach to averaging that maintains the worst-case convergence rate theory of PR averaging, while matching and often exceeding the performance of schedule-based approaches”, demonstrated on 28 problems. Schedule-Free methods show strong performance, matching or out-performing heavily-tuned cosine schedules. The formulation of this Schedule-Free SGD is:

\[\begin{align*} y_t = \, & (1 − β) z_t + β x_t, \\ z_{t+1} = \, & z_t − γ∇f(y_t, ζ_t), \\ x_{t+1} = \, & (1 − c_{t+1}) x_t + c_{t+1} z_{t+1}, \\ \end{align*}\]where \(f(y_t, ζ_t)\) is the loss between model output and random variable \(ζ\), \(c_{t+1}\) is defined as before and \(z_1 = x_1\). “Note that with this weighting, the \(x\) sequence is just an online equal-weighted average of the \(z\) sequence. This method has a momentum parameter \(β\) that interpolates between Polyak-Ruppert averaging (\(β = 0\)) and Primal averaging (\(β = 1\)). Primal averaging is the same as PR except that gradient is evaluated at the averaged point \(x\), instead of \(z\) (see paper for definition), and “maintains the worst-case optimality of PR averaging but is generally considered to converge too slowly to be practical (Figure 2).”

The main point is: “The advantage of our interpolation is that we get the best of both worlds. We can achieve the fast convergence of Polyak-Ruppert averaging (since the \(z\) sequence moves much quicker than the \(x\) sequence), while still keeping some coupling between the returned sequence \(x\) and the gradient-evaluation locations \(y\), which increases stability (Figure 2). Values of β similar to standard momentum values \(β ≈ 0.9\) appear to work well in practice.”

2023 Training and inference of large language models using 8-bit floating point

The paper “presents a methodology to select the scalings for FP8 linear layers, based on dynamically updating per-tensor scales for the weights, gradients and activations.” The FP8 representation tested is the FP8E4 and FP8E5, for 4 and 5 bits of exponent, respectively. Despite the naming, intermediate computation is performed on 16 bits. The bias and scaling operations are applied to the exponent, not the final value. They tested two scaling techniques, AMAX (described before), or SCALE (keeping scale constant), and noticed there isn’t a major degradation. Results this fp8 to fp 16, but do not compare to bfloat16 because hardware was not available at the time. Algorithm in Figure 3. Note to self: I dont understand how so operations in float8 can be faster than half the executions in bfloat16 (because the workflow is so large); so it’s probably only faster than float16 because also requires a longer workflow with scaling (?).

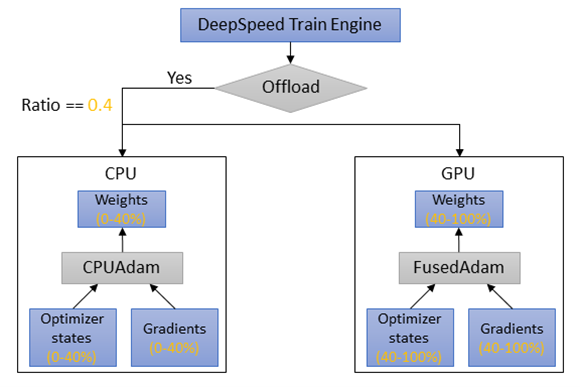

2023 DeepSpeed ZeRO-Offload++: 6x Higher Training Throughput via Collaborative CPU/GPU Twin-Flow

“System efficiency is still far from optimal when adopting ZeRO-Offload in some scenarios. Especially in the cases like small batch training, model that could not fit into GPU memory but not orders-of-magnitude bigger than GPU memory capacity, CPU offload not only introduce long end-to-end latency, but also underutilize GPU computation resources.” With that in mind, Zero-Offload++ introduces 3 fetures:

- Twin-Flow: instead having an all-or-nothing policy (ie offload all or none of) in the values to be offloaded, “Twin-Flow allows a portion of optimizer states to be held in CPU memory and the other portion of optimizer states remaining in GPU memory. When optimization step is triggered, both CPU and GPU can do parameter updates simultaneously.” The user can choose the percentage of ratio of parameters in CPU and GPU. “Therefore, with Twin-Flow, we can achieve decent GPU memory and core utilization rate, at the same time reduce training iteation time in optimizer offloading cases.”

- MemCpy reduction: details not available yet;

- CPUAdam optimization: details not available yet;

2023 ZeRO++: Extremely Efficient Collective Communication for Giant Model Training, Microsoft

DeepSpeed ZeRO’s compute throughput is limited by the high communication cost from gathering weights in forward pass, backward pass, and averaging gradients. This is mostly prominent on clusters with low-bandwidth, and at very small batch sizes per GPU.

Background, communication pipeline: “Assume the model size as 𝑀. During the forward pass, ZeRO conducts an all-gather operation to collect all the parameters (𝑀) needed to train for all model layers. In the backward pass, ZeRO re-collects parameters (𝑀) with all-gather first, then each GPU can compute local gradients. After that, ZeRO operates reducescatter function to aggregate and redistribute gradients (𝑀) across accelerators. In total, ZeRO has a total communication volume of 3𝑀, spreads evenly across 2 all-gather and 1 reduce-scatter.”

The paper introduces three communication reduction techniques, packed as ZeRO++:

- Quantized Weight Communication for ZeRO (qwZ): perform block quantization of the forward all-gather, converting weights from FP16 (2 bytes) to INT8 (1 byte). The main improvement is to replace the typical quantization algorithm (multiplying all parameters by a scalar), by a quantization per block (ie per parameter subset) that includes multiplication by a factor and shifting values by another factor;

- Hierarchical Weight Partition for ZeRO (hpZ): data remapping that trades-off communication for more memory and reduces communication overhead of all-gather on weights during backward. Instead of having weights distributed across GPUs, we maintain a full copy on each machine, allowing us to replace the expensive cross-machine all-gather on weights with a faster intra-machine all-gather.

- Quantized Gradient Communication for ZeRO (qgZ): replaces the gradients reduce-scatter collective, by doing (1) block-based quantization of gradients to

INT4during communication to reduce the communication size, and recovering the full precision before the reduction operator to preserve training accuracy. Having a fully block-based quantization approach like in (1) was also considered but led to high precision loss and a high error propagation across layers during backpropagation.

The results sections claims that ZeRO++ yields a communication reduction of 4x compared to ZeRO-3, leading to up to 2.16x higher compute throughput on 384 GPUs.

2023 QLoRA: Efficient Finetuning of Quantized LLMs, Washington Uni

“An efficient finetuning approach that reduces memory usage enough to finetune a 65B parameter model on a single 48GB GPU while preserving full 16-bit finetuning task performance. QLORA backpropagates gradients through a frozen, 4-bit quantized pretrained language model into Low Rank Adapters (LoRA). QLORA introduces multiple innovations designed to reduce memory use without sacrificing performance: (1) 4-bit NormalFloat, an information theoretically optimal quantization data type for normally distributed data that yields better empirical results than 4-bit Integers and 4-bit Floats. (2) Double Quantization, a method that quantizes the quantization constants, saving an average of about 0.37 bits per parameter (approximately 3 GB for a 65B model). (3) Paged Optimizers, using NVIDIA unified memory to avoid the gradient checkpointing memory spikes that occur when processing a mini-batch with a long sequence length. We use QLORA to finetune more than 1,000 models, [and] results show that QLoRA finetuning on a small high-quality dataset leads to state-of-the-art results, even when using smaller models than the previous SoTA”. Notes to self:

- 4-bit NormalFloat Quantization rounds values to the nearest bin (in a 4-bit representation) where each bin is a normal distribution quantile. It’s an expensive procedure, so they use fast quantile approximation algorithms such as SRAM. It also yields high errors for outliers.

2023 Better speech synthesis through scaling (TorToise), James Bekter

The paper describes a way to apply ML for generating images to the speech synthesis. This result is TorToise, an expressive, multi-voice text-to-speech system. So far, TTS models were hard to train eficiently due to high sampling rate, unavailability of large datasets, or encoder-decoder challenges.

Background: most modern text-to-speech systems operate on speech data that is encoded as a MEL spectrogram. Because of this, most efforts focus on the high-quality decoding of MEL spectrograms back into audio waveforms, a.k.a. a vocoder or a MEL inverter. The author dives in the state-of-the-art autoregressive transformers and DDPMs models:

- DALL-E, a transformer model with a (quadratic complexity) full-sequence self-attention, that showed how an autoregressive decoder can be applied to text-toimage generation. The author believes that the “VQVAE decoder used by DALL-E is principally responsible for the blurry incoherence exhibited by most of it’s samples”.

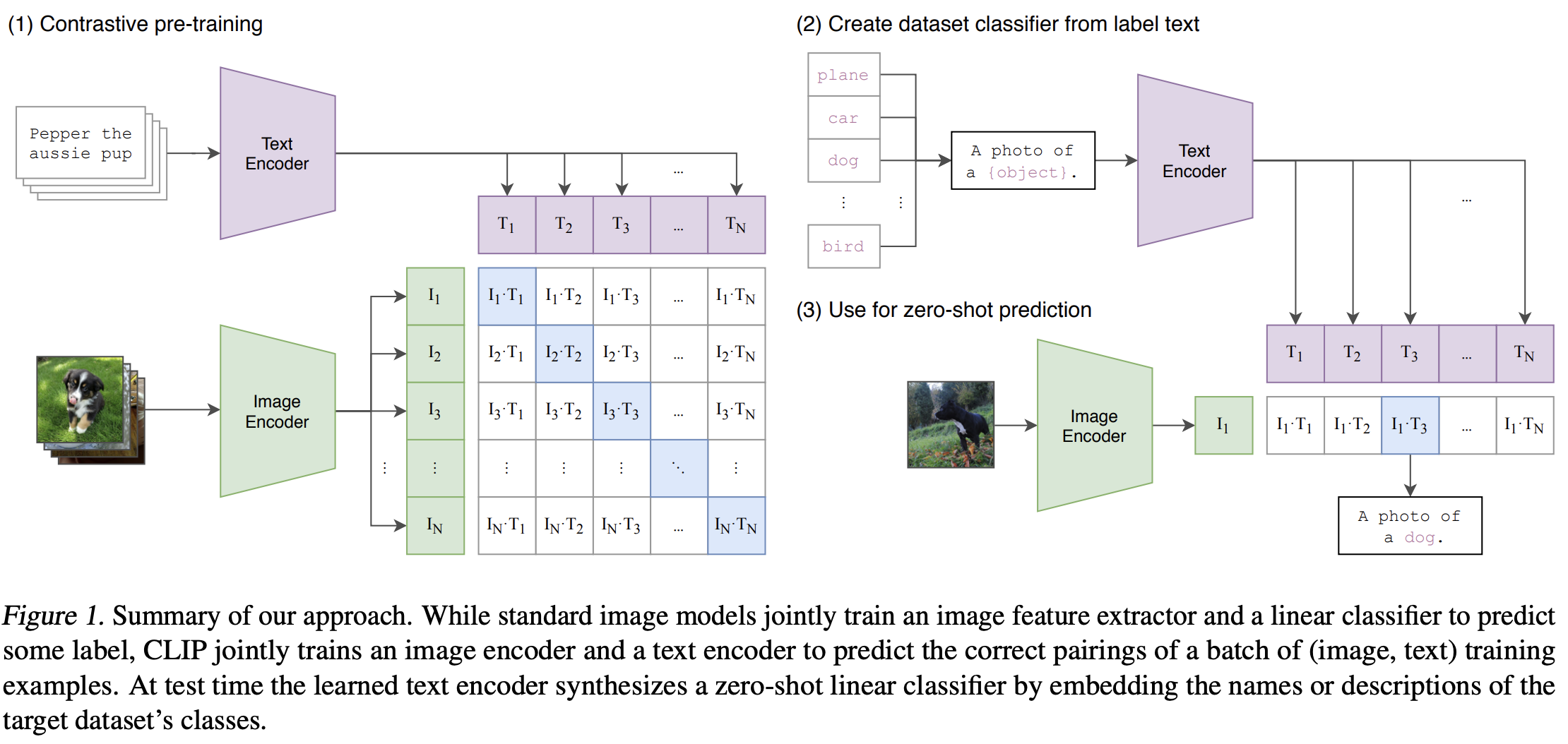

- DALL-E also introduced the process of re-ranking, that samples from the autoregressive model and picks the best output for downstream use. Re-ranking requires a a strong discriminator to tell good from bad text/image pairings. CLIP was used for this purpose.

- Denoising diffusion probabilistic models (DDPMs) generate crisp high quality images, and are effective on using low-quality signals to reconstruct the high-dimensional space where those signals derived from. However, DDPMs rely on fixed output shapes, know beforehand. Thus, they “ cannot learn to convert text into audio signals because they cannot solve the implicit alignment problem between text and audio”. Also, DDPMs must be sampled from over multiple iterations, leading to high compute cost and latency.

With that in mind: TorToise works by joining autoregressive decoders and DDPMs: “the autoregressive model will be used to convert a sequence of text tokens to a sequence of tokens representing the output space (in our case, speech tokens). The DDPM will then be used to decode these tokens into a high quality representation of speech.” In practice, for Text-To-Speech, we train the following neural networks:

- An auto-regressive model on text tokens that yields the probability of each audio token;

- A contrastive model that ranks outputs of the autoregressive decoder. DALL-E uses CLIP (for images), but TorToise uses Contrastive Language-Voice Pretrained Transformer (CLVP, for TTS).

- A DDPM to convert speech tokens back into speech spectrograms;

The inputs of the auto-regressive and DDPM models include (or are conditioned to) an additional speech conditioning input, which is one or more audio clips (MEL spectograms) of the same speaker as the target. This allows the model to learn “infer vocal characteristics like tone and prosody” are desired in the target output audio. Finally, they apply the TorToise trick: the DDPM is first trained on converting discrete speech codes into MEL spectrograms, and then fine-tuned on the latent space of the AR model outputs instead of the speech codes. “The logic here is that the AR latent space is far more semantically rich than discrete tokens. By fine-tuning on this latent space, we improve the efficiency of the downstream diffusion model”

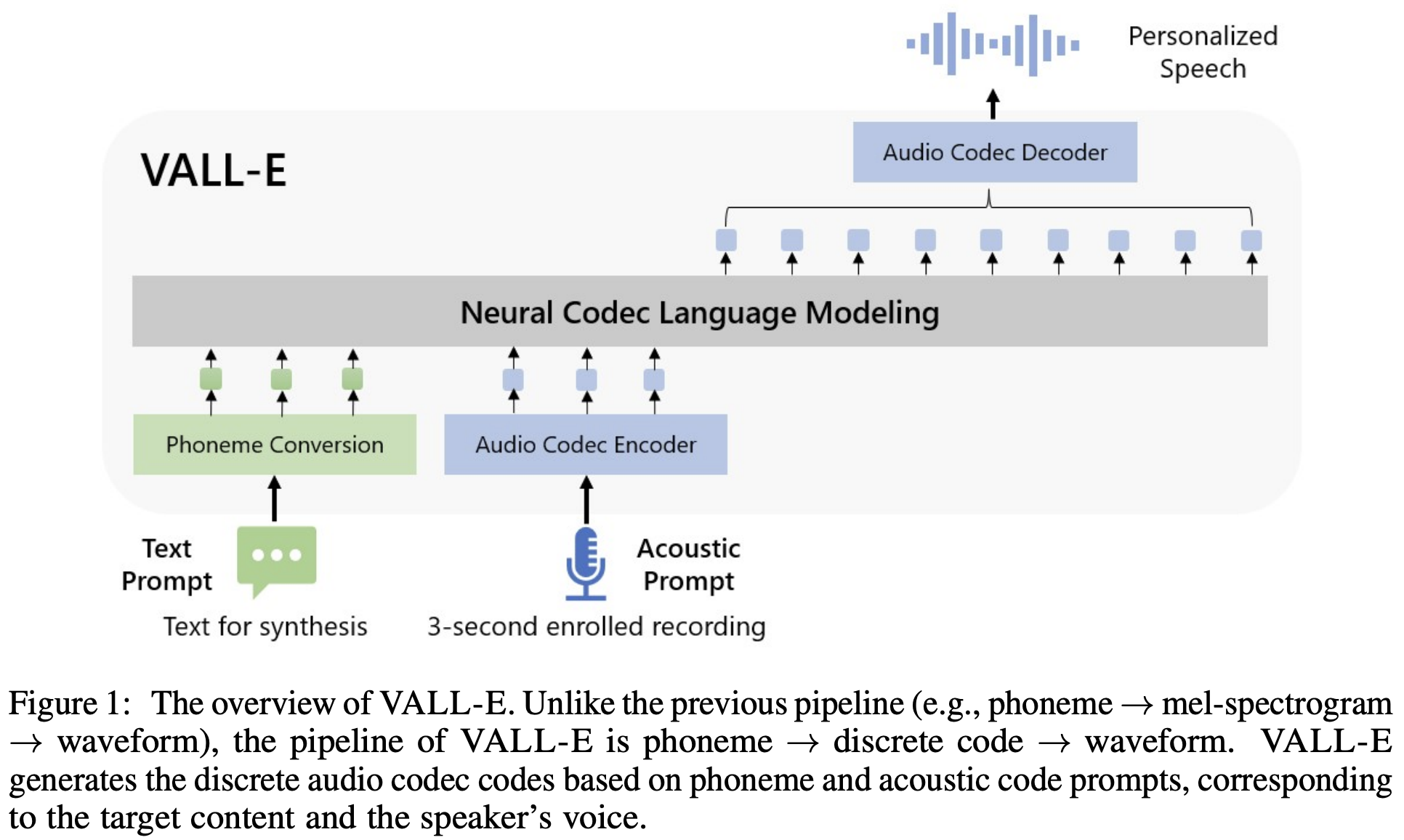

2023 Neural Codec Language Models are Zero-Shot Text to Speech Synthesizers (VALL-E), OpenAI

The paper introduces a pipeline for text-to-speech translation (TTS), based on a neural codec language model (VALL-E) using discrete codes (encode/decode embeddings) derived from an off-the-shelf neural audio codec model (Encoded, Défossez et al., 2022). This mode treats TTS as a conditional language modeling task rather than continuous signal regression as in previous work. In practice, contrarily to e.g. AudioLM, a generative audio-to-audio / speech-to-speech model that predicts future audio from input audio, VALL-E is a TTS mode that takes as input a fixed-size text representation and the audio of the first 3 seconds of the text, and tries to predict the future audio that matches the remaining of the input text. VALL-E uses an audio codec code as intermediate representation and language model as objective, contrary to previous models using mel spectrogram as intermediate representaion and continuous signal regression as objective. VALL-E is trained with the LibriLight dataset, consisting of 60K hours of English speech with over 7000 unique speakers. This dataset is audio-only, so the authors employ a speech recognition model to generate the (text) transcriptions.

Background, quantization, tokenizer and encoding: audio is typically stored as a sequence of 16-bit integer values, therefore a generative model is required to output \(2^{16}\) = 65536 probabilities per timestep to synthesize the raw audio. Added to the high output size, its long sequence length makes it more intractable for audio synthesis. Therefore, speech quantization is required to compress integer values and sequence length. Common methods are \(\mu\)-law, vector quantization (HuBERT, vq-wav2vec), k-means/self-supervised method, etc. As audio tokenizer, VALL-E uses a pre-trained neural audio codec model, EnCodec, a convolutional encoder-decoder model, whose input and output are both 24 kHz audio across variable bitrates. The encoder produces embeddings at 75 Hz for input waveforms at 24 kHz, which is a 320-fold reduction in the sampling rate. Each embedding is modeled by residual vector quantization (RVQ), with eight hierarchy quantizers with 1024 entries each as shown in Figure 2.

Model architecture: formally speaking, \(Encodec(y) = C^{T \times 8}\), where \(C\) represents the two-dimensional acoustic code matrix (the 8-channel audio embeddings), and \(T\) is the downsample utterance length. Each row in \(C\) represents the eight codes for a given time frame. After quantization, the neural codec decoder is able to reconstruct the waveform, i.e. \(Decodec(C) ≈ \hat{y}\). Given an accoustic prompt matrix \(\hat{C}^{T \times 8}\), the optimization objective of the TTS model is \(max\, p(C \mid x, \hat{C})\), where \(x\) is the corresponding phoneme transcription. I.e. the model learns to extract the content and speaker information from the phoneme sequence and the acoustic prompt, respectively.

There are two models, that refer to the two inference steps:

- an auto-regressive (AR) model, a transformer decoder-only architecture, conditioned on the phoneme (text) and accoustic prompt (3-second audio), that gives the discrete tokens of the audio from the first quantizer (Formula 1).

- a non auto-regressive (NAR), a transformer decoder will full mask, that regressively predicts the remaining 7 quantizers from the first one (Formula 2).

Note to self: for the use case of synthethising audio in a different language, i.e. that differs from the 3-sec input language and text, see VALL-E X.

2023 High-Fidelity Audio Compression with Improved RVQGAN, Descript Inc.

An audio encoder-decoder that supposedly beats Meta’s encodec. Achieved by combining advances in high-fidelity audio generation with better vector quantization techniques from the image domain, along with improved adversarial and reconstruction losses. Methods:

- to account for periodicity in audio inputs, they adopted the snake activation function for frequency \(\alpha\) as \(snake(x) = x + \frac{1}{α} sin^2 (αx)\).

- vanilla VQ-VAEs struggle from low codebook usage due to poor initialization, leading to a significant portion of the codebook being unused. This leads to to poor reconstruction quality. To address this issue, they use two techniques: (1) factorized codes that decouples code lookup and code embedding, by performing code lookup in a low-dimensional space (section 3.2) and (2) L2-normalization of the encoded and codebook vectors converts euclidean distance to cosine similarity, which is helpful for stability and quality.

- state-of-the-art applying quantizer dropout degrades the audio reconstruction quality at full bandwidth. To overcome it, they instead apply quantizer dropout to each input example with some probability \(p=0.5\).

- an improved STFT discriminator at multiple time-scales, that works better in practice and leads to improved phase modeling, compared to Encodec and Soundstream.

- for frequency domain reconstruction loss, they use a mel-reconstruction loss to improve stability, fidelity and convergence speed; and multi-scale spectral losses to encourage modeling of frequencies in multiple time-scales. For adversarial loss, they use HingeGAN. For codebook learning, they use commitment losses with stop-gradients from the original VQ-VAE formulation. All these losses are weighted to sum up to the final loss.

2023 Llama 2: Open Foundation and Fine-Tuned Chat Model, Meta

LLama 2 is a collection of pretrained and fine-tuned large language models (LLMs) ranging in scale from 7 billion to 70 billion parameters. Llama 2-Chat is a finetuned LLM optimized for dialogue use cases. The models outperform open-source chat models, and based on human evaluations for helpfulness and safety, it outperforms open-source models and appear to be on par with closed-source models (although may not be a suitable substitute). Results on safety human evaluation for Llama 2-Chat are presented in Figure 3. The train dataset is only publicly available sources, which does not include data from Meta’s products or services, or sources that may include users’ personal information. Table 2 presents the GPU compute hours, power consumption and carbon emissions of each model

The pretraining setting and model architecture are adopted from Llama 1, i.e. bytepair encoding (BPE), pre-normalization via RMSNorm, SwiGLU activations, rotary positional embeddings, AdamW optimizer, cosine learning rate scheduler. However, the primary architectural differences from Llama 1 include increased context length and grouped-query attention (GQA).

The finetuning was performed with supervised fine-tuning (Section 3.1), initial and iterative reward modeling (Section 3.2.2) and RLHF (Section 3.2.3). As drawback of RLHF, “initial RLHF models tended to forget the initial instruction after a few turns of dialogue (Figure 9, below, left). To address these limitations, we propose Ghost Attention (GAtt), a very simple method inspired by Context Distillation (Bai et al., 2022b) that hacks the fine-tuning data to help the attention focus in a multi-stage process”. In Gatt, ghost tokens are introduced at specific intervals or positions, and do not represent actual data but serve as intermediate “proxies” to summarize information across groups of tokens. (Figure 9, below, right).

2023 LLaMA: Open and Efficient Foundation Language Models, Meta

LLaMa is a collection of Large Language Models (LLM) with 7B to 65B parameters trained in public datasets, with performance superior to GPT-3 and comparable with Chinchilla-70B and PaLM-540B. Training is inspired by the Chinchilla scaling laws. The datasets used for the pre-training data are presented in Table 1, with training hyperparameters in Table 2. String are tokenized using the bytepair encoding (BPE) algorithm, with circa 1.4T tokens after tokenization.

The models architecture is made of several improvements over the original Transformer:

- Pre-normalization [GPT3]: training stability is improved with RMSNorm normalization at the input of each transformer sub-layer, instead of output.

- SwiGLU activation function [PaLM]: ReLU activation is replaced with SwiGLU to improve performance, with a dimension of \(\frac{2}{3} 4d\) instead of \(4d\) as in PaLM.

- Rotary Embeddings [GPTNeo]: positional embeddings are replaced by rotary positional embeddings (RoPE) at each layer of the output.

- Optimization performed with AdamW optimizer with \(β_1 = 0.9\), \(β2 = 0.95\) and \(eps = 10^{−5}\).

- Cosine learning rate schedule with a warmup of \(2000\) steps, a weight decay of \(0.1\), a gradient clipping of \(1.0\) and a final learning of \(10%\) of the initial value.

- Efficient causal multi-Head attention achieved by not storing the attention weights and not computing the key/query scores that are masked due to the causal nature of the language modeling task.

- Activation checkpointing was implemented to reduce memory. Yet it required manually implementing the Pytorch backward propagation function for the Transformer (insted of PyTorch autograd). This also required model and sequence parallelism (why?).

- Overlap of the computation of activations and the communication between GPUs over the network, to reduce latency.

2023 Sparks of Artificial General Intelligence: Experiments with an early version of GPT-4, Microsoft

A summary paper reporting early results of the experiments with GPT-4 when it was still in active development by OpenAI. The authors “demonstrate that, beyond its mastery of language, GPT-4 can solve novel and difficult tasks that span mathematics, coding, vision, medicine, law, psychology and more, without needing any special prompting. Moreover, in all of these tasks, GPT-4’s performance is strikingly close to human-level performance”. The bulk of the paper contains dozens of examples that compare GPT-4 and Chat-GPT and demonstrate that GPU-4 surpasses ChatGPT in performance, in code generation, audio generation (output as musical notes), drawings (SVG, TIKZ), and mathematical resolutions (LaTeX). As weaknesses, besides the regular hallucinations it was also observed:

- Incapacity of planning correctly, when planning is not a linear path.

- Occasional arithmetic mistakes on long expressions (without tool use), highlighting limits in exact computation.

- Trained on past information only, without real-time/temporal awareness.

- lack of rigorous algorithms e.g.

What is the 11th letter of "abacadab"? … the 11th letter is "b." - Analogical reasoning can reproduce social stereotypes present in training data.

But these can be overcome by including external APIs on training and making them in the query e.g.:

2023 Retentive Network: A Successor to Transformer for Large Language Models, Microsoft and Tsinghua University

(note: a simpler summary video of RetNet can be found here)

RetNet is a multi-scale retention mechanism to substitute multi-head attention in Transformers, which has three computation paradigms:

- parallel framework, for training parallelism that utilizes GPU devices fully.

- recurrent framework for low-cost \(O(1)\) inference, which improves decoding throughput (8.4x improvement over Transformer), latency (15.6x), and GPU memory (3.4x) without sacrificing performance, on Figure 1.

- a chunkwise recurrent representation that can perform efficient long-sequence modeling with linear complexity, where each chunk is encoded parallelly while recurrently summarizing the chunks. It allows encoding each local block for computation speed while recurrently encoding the global blocks to save GPU memory

Retentive network (RetNet) is a stack of \(L\) identical blocks, which follows a similar layout (i.e., residual connection, and pre-LayerNorm) as in Transformer. Each RetNet block contains two modules: a multi-scale retention (MSR) module, and a feed-forward network (FFN) module. The MSR module calls the tokens in a sequence in an auto-regressive manner. The input vector is first created as \(X_0\) in the shape of sequence length by hidden domain size. Then we calculate contextualized vector representations \(X_n\) for each layer of the RetNet. Retention heads can be represented in two alternative ways:

- in the parallel representation, where \(Retention(X) = Q K\intercal \dot D)V\) similar to the transformer but with an extra matrix \(D\) (Eq. 5). This is befenicial for parallel training.

- in the recurrent representation, it is written as a recurrent neural net (RNN) which is beneficial for inference, and \(Retention(X_n)=Q_n S_n\) where \(S_n\) depends on the previous term \(S_{n-1}\).

- a hybrid form combining the previous two representations is also possible to accelerate training on large sequences. Input sequence is divided into chunks. Within each chunk, the computation is performed in the parallel representation. Cross-chunk information is passed in the recurrent representation.

Finally, the model uses \(h = d_{model}/d\) retention heads in each layer, where \(d\) is the head dimension. The heads use different parameter matrices \(W_Q, W_K, W_V \in \mathbb{R}^{d \times d}\) and scalar \(γ\) per head. The overall architecture for a given layer \(l\) of the RetNet is then \(Y_l = MSR(LayerNorm(X_l)) + X_l\) and \(X_{l+1} = FFN(LN(Y_l)) + Y_l\), ie similar to a regular transformer but replacing the attention by a retention head.

2023 RoFormer: Enhanced Transformer with Rotary Position Embedding (Rotary Embedding, RoPe)

Traditional positional encoding methods, like sinusoidal or learned embeddings, struggle to generalize well to long sequences because they either: (1) Use absolute positions that are fixed and cannot model relative relationships effectively. (2) Lack a mechanism to extrapolate beyond the sequence lengths seen during training. Rotary embeddings address these issues by encoding relative positional information directly into the attention mechanism, improving efficiency and generalization. “RoPE encodes the absolute position with a rotation matrix and meanwhile incorporates the explicit relative position dependency in self-attention formulation”.

Rotary embeddings modify the query (𝑄) and key (K) embeddings in self-attention. They do this by applying rotations to the embeddings based on the positions of tokens in the sequence.

\[R(x) = \begin{bmatrix} \cos\theta & -\sin\theta \\ \sin\theta & \cos\theta \end{bmatrix} \cdot \begin{bmatrix} x_1 \\ x_2 \end{bmatrix}\]The rotation angle \(𝜃_𝑝\) for position \(p\) is determined as \(𝜃_𝑝 = p \, w\), where \(w\) is a frequency determined by the dimensionality and scaling factors. Important bit: \(x_1\) and \(x_2\) are the input \(x\) expressed in the 2D coordinates. To handle a \(d\)-dimensional input, we split \(x\) into pairs of dimensions \([ (x_1, x_2), \, (x_3, x_4), \, \dots, \, (x_{d-1}, x_d)]\), apply the 2D rotation matrix to each pair, and then concatenate the results to reconstruct the rotated vector. If \(x\) has an odd dimensionality \(d\), the extra dimension is often left unrotated.

2023 Operator Fusion in XLA: Analysis and Evaluation, UToronto

Kernel fusion is the most significant optimization operation in XLA. This paper details XLA and key compiler passes of XLA’s source code. It also presents the speedup that kernel fusion can deliver, and what low-level effects it has on hardware.

2023 LongNet: Scaling Transformers to 1,000,000,000 Tokens, Microsoft and Xi’an Jiaotong University

LongNet is a Transformer variant that can scale the sequence length up to 1B tokens, and without sacrificing the performance on shorter sequences. This overcomes current limitations of attention size in regular transformers, that requires a tradeoff between computational complexity and the model expressivity. The main trick is based on the dilated attention, which is similar to strided attention but with exponentially increasing strides (e.g., attending to tokens at distances 1, 2, 4, 8, etc.).

2023 FlashAttention-2: Faster Attention with Better Parallelism and Work Partitioning

“FlashAttention is still not nearly as fast as optimized matrix-multiply (GEMM) operations, reaching only 25-40% of the theoretical maximum FLOPs/s. We observe that the inefficiency is due to suboptimal work partitioning between different thread blocks and warps on the GPU, causing either low-occupancy or unnecessary shared memory reads/writes. We propose FlashAttention-2, with better work partitioning to address these issues. In particular, we (1) tweak the algorithm to reduce the number of non-matmul FLOPs (2) parallelize the attention computation, even for a single head, across different thread blocks to increase occupancy, and (3) within each thread block, distribute the work between warps to reduce communication through shared memory. These yield around 2× speedup compared to FlashAttention, reaching 50-73% of the theoretical maximum FLOPs/s on A100 and getting close to the efficiency of GEMM operations. We empirically validate that when used end-to-end to train GPT-style models, FlashAttention-2 reaches training speed of up to 225 TFLOPs/s per A100 GPU (72% model FLOPs utilization).”

2023 Flow Matching for Generative Modeling

Flow Matching is a a simulation-free approach for training CNFs (Continuous Normalizing Flows) that is compatible with a general family of Gaussian probability paths for transforming between noise and data samples, as required by the reverse process in diffusion models. “Furthermore, Flow Matching opens the door to training CNFs with other, non-diffusion probability paths. An instance of particular interest is using Optimal Transport (OT) displacement interpolation to define the conditional probability paths. These paths are more efficient than diffusion paths, provide faster training and sampling, and result in better generalization”. See a good explanation in this Cambridge ML group post</summary> .

2022 Titans: Learning to Memorize at Test Time, Google Research

A model that utilizes recurrent logic and attention, like mamba. From the abstract: “We present a new neural long-term memory module that learns to memorize historical context and helps an attention to attend to the current context while utilizing long past information. We show that this neural memory has the advantage of a fast parallelizable training while maintaining a fast inference. From a memory perspective, we argue that attention due to its limited context but accurate dependency modeling performs as a short-term memory, while neural memory due to its ability to memorize the data, acts as a long-term, more persistent, memory.”

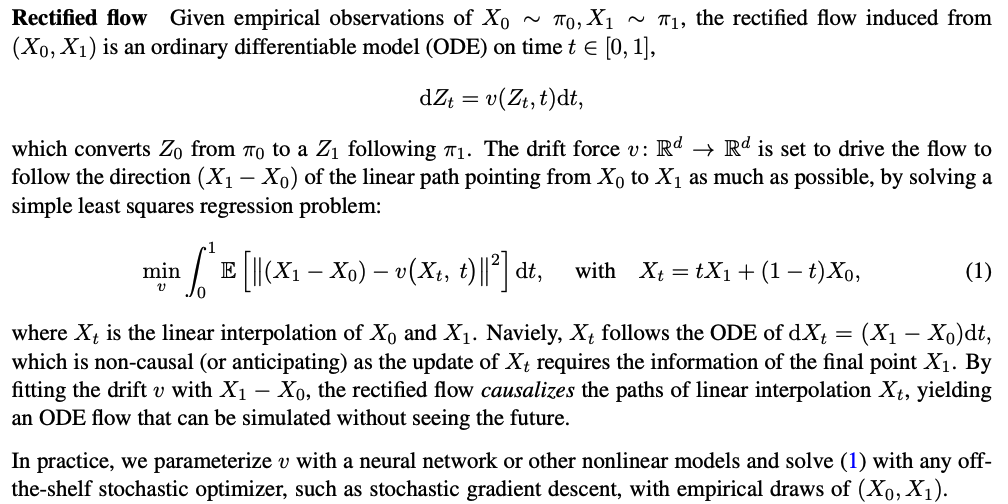

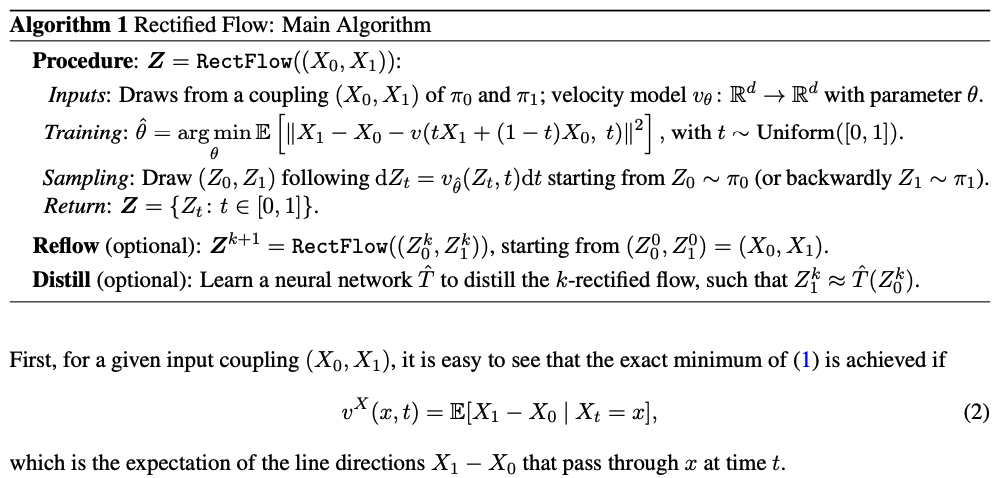

2022 Flow Straight and Fast: Learning to Generate and Transfer Data with Rectified Flow

Rectified flows aim at reducing the number of steps when transitioning between two distributions. This is important for e.g. diffusion models where we perform inference by performing \(T\) sampling steps and we want to do it in less steps, by finding a flow between interleaved steps. The rectified flow is an ODE model that transport distribution \(π_0\) to \(π_1\) by following straight line paths as much as possible. The straight paths are preferred both theoretically because it is the shortest path between two end points, and computationally because it can be exactly simulated without time discretization

2022 Tensor Programs V: Tuning Large Neural Networks via Zero-Shot Hyperparameter Transfer (\(\mu\)Transfer), Microsoft

Maximal Update Parametrization (muP) showed that many optimal hyper-parameters remain constant as the mode size changes: “When (layer) width is large, every activation vector has roughly iid coordinates, at any time during training. Using Tensor Programs, we can recursively calculate such coordinate distributions, and consequently understand how the neural network function evolves”.

With that in mind, here, here they propose a hyper-parameter tuning paradigm called muTransfer: “parametrize the target model in muP, tune the HP indirectly on a smaller model, and zero-shot transfer them to the full-sized model”.

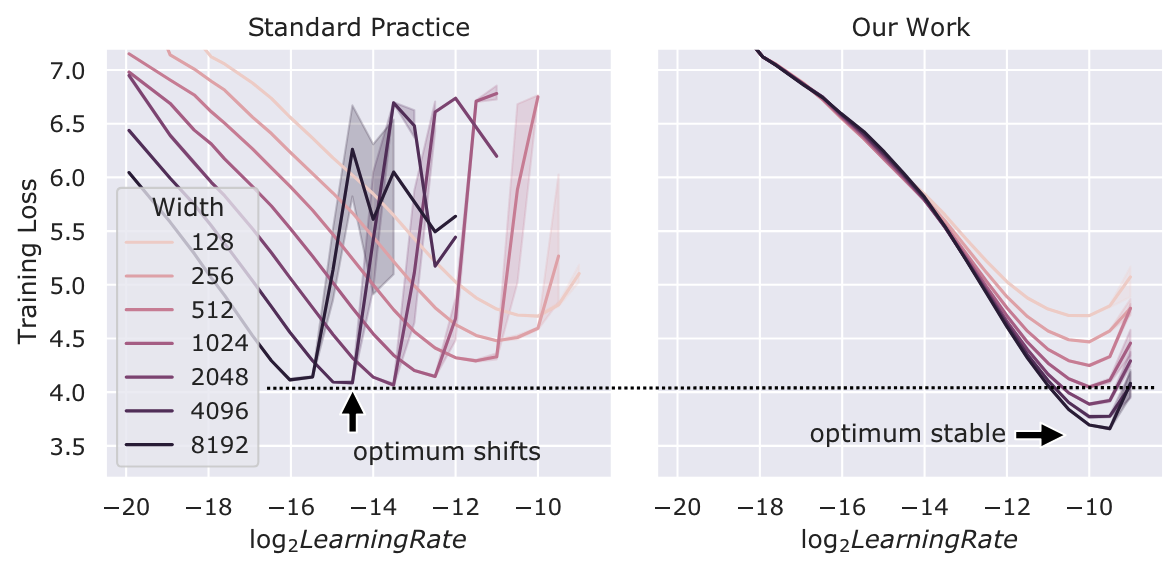

Figure 1: Training loss against learning rate on Transformers of varying \(d_{model}\) trained with Adam. Conventionally and in contrast with our technique, different widths do not share the same optimal hyperparameter; wider networks do not always perform better than narrower ones; in fact they underperform the same-width networks in our technique even after tuning learning rate (see dashed line).

Hyperparameters That Can Be µTransferred, Not µTransferred, or µTransferred Across (Depth), with a few caveats discussed in Section 6.1. * means empirically validated only on Transformers, while all others additionally have theoretical justification.

- µTransferable: optimization related (learning rate, momentum, Adam beta, LR schedule, etc), init (per-layer init variance), parameter multipliers (multiplicative constants after weight/biases, etc), etc

- Not µTransferable: regularization (dropout, weight decay, etc)

- µTransferred Across (Depth): width, depth, batch size, training time, seq length

2022 Self-Attention Does Not Need (O(n^2)) Memory

Rabe & Staats formalize the idea that self-attention can be computed without storing the full (n \times n) attention matrix by using a streaming / online computation of the softmax-normalized attention. This is a conceptual ancestor of several practical kernels: it gives the mathematical justification for computing attention in blocks while maintaining numerical stability and correctness.

Why it still matters in modern systems papers:

- It provides a clean argument for why “don’t materialize (QK^\top)” is not just an approximation—it can be exact.

- It underpins many attention kernels that trade memory for compute and enable long-context attention to be feasible.

2022 DeepSpeed-Inference: Enabling Efficient Inference of Transformer Models at Unprecedented Scale (SC 2022)

DeepSpeed-Inference is a systems paper about getting Transformer inference to scale in practice: kernel fusion (to reduce memory traffic and launch overhead), parallelism strategies, and memory optimizations that allow very large models to run efficiently.

In the context of fusion-heavy related work:

- DeepSpeed-Inference aggressively fuses compute (Transformer kernels, projections, etc.) and optimizes the inference runtime, but generally keeps communication as NCCL collectives outside of those kernels.

- This makes it a useful baseline class: it shows what you can get from strong kernel engineering and runtime scheduling without changing the underlying communication model.

Results / takeaways: the paper demonstrates that systematic kernel/runtime optimizations can unlock large-scale inference and high throughput, and it established many techniques that later LLM serving stacks built on.

2022 DeepSpeed-MoE: Advancing Mixture-of-Experts Inference and Training to Power Next-Generation AI Scale (ICML 2022)

DeepSpeed-MoE is an influential MoE system that focuses on making expert models train and run efficiently by addressing the MoE-specific bottlenecks: token routing, all-to-all communication, and balancing compute/communication across experts. It includes runtime techniques to overlap communication with local work and reduce overhead in the MoE pipeline.

How it compares to later MoE system lines (MegaScale-*):

- DeepSpeed-MoE provides a general MoE framework and many practical optimizations, but later production-scale systems often introduce more specialized parallelism strategies and communication libraries to handle extreme scale.

- DeepSpeed-MoE is also representative of approaches that keep collectives “standard” (NCCL-style), whereas newer kernel-level work explores in-kernel collectives and fine-grained overlap.

Results / takeaways: the paper demonstrates that MoE can scale effectively with careful engineering, and it helped popularize MoE as a practical path to scaling model capacity without proportional compute.

2022 DeepSpeed Inference: Enabling Efficient Inference of Transformer Models at Unprecedented Scale, Microsoft DeepSpeed

Inference kernels must therefore achieve high memory bandwidth utilization and high compute utilization at small batch sizes, whereas training kernels simply need to achieve high compute utilization at much larger batch sizes. This makes developing inference kernels quite challenging. DeepSpeed Inference consists of two components:

- DeepSpeed Transformer: DeepSpeed Inference can automatically scale a dense transformer model to multiple devices by partitioning transformer operators across multiple devices while also adding appropriate communication operations needed across GPUs. Under the hood, it leverages the single GPU kernels to maximize per GPU memory bandwidth utilization, while using NCCL all-reduce collectives to perform the necessary across GPU communication. This allows DeepSpeed Inference to achieve excellent aggregate memory bandwidth utilization across several GPUs with a node. However, tensor slicing can not be scaled efficiently beyond a single node due to significant communication overhead. Thus to further scale to multi-node systems, DeepSpeed Inference uses pipeline parallelism. DeepSpeed Transformer includes three transformer modules:

- a single GPU transformer kernels for minimizing latency and maximizing throughput via memory-bandwidthcentric fusion schedules and GeMM kernels (Sec. III). This is described below.

- A many-GPU dense transformer inference system that combines tensor-parallelism to minimize latency with inference optimized pipeline parallelism schedules and memory optimizations to maximize throughput (Sec. IV). The model and pipeline parallelism techniques are then applied on top of the single GPU kernels.

- A massive-GPU sparse (MoE) model inference system that combines: i) expert, data, and tensor parallelism, ii) novel communication optimizations and iii) sparse kernel optimizations to scale sparse inference on trillions of parameters across hundreds of GPUs (Sec. V). Expert parallelism is also introduced, where all-to-all can happen within just the subset of devices that share the same tensor-slicing rank, since the data across tensor-parallel ranks are replicated. The sparse tensor representation in the gating function and sparse einsum operators introduce a significant latency overhead, optimized with kernel fusion.

- ZeRO-Inference that leverages CPU, NVMe and GPU memory along with GPU compute to make massive model inference accessible with limited resources (Sec. VI). An important design decision is how to apportion GPU memory among model weights, inference inputs, and intermediate results. One approach is to pin as much of the model weights as possible into GPU memory, and fetch the remainder (from DRAM or NVMe) when needed for computation. The big downside is that allow for a small batch size. ZeRO-Inference adopts a different approach that pins the model weights either in DRAM (if large enough) or NVMe, and streams each layer into GPU memory for computation when needed.

The single GPU transformer kernels introduce two techniques:

- Deep-Fusion to reduce kernel-invocation and data-movement overheads by fusing multiple kernels beyond element-wise operation. The rationale is: on GPU, if a data produced by a thread-block is consumed by a different one, a global memory synchronization is needed which invokes a new kernel. To avoid the need for a global synchronization, Deep-Fusion tiles the computation-space along dimensions of the iteration space which incur no cross-tile data-dependencies and executes them in parallel across different thread-blocks. The dimensions of the computation-space which does contain data dependencies are not tiled, and instead processed by the same thread-block. After this tiling, two operators can be fused using DeepFusion if each tile of the second operator depends on exactly one output tile of the first operator. Deep-Fusion can fuse not only element-wise operations but also reductions, data transpositions, and GeMMs as long as there are no cross-tile dependencies.

- a Custom GeMM implementation designed to be fusable with Deep-Fusion while achieving maximum memory bandwidth utilization. “We first tile the computation along the output dimension. That allows us to implement GeMM using a single kernel by keeping the reduction within a tile” Then, with the aforementioned tiling strategy, each warp in a thread block is responsible for producing a partially reduced result for a tile of outputs and a final reduction is needed across all the warps within the thread block. To avoid having to reduce the partial results in shared memory, we perform a single data-layout transpose in shared memory such that partial results of the same output element are contiguous in memory, and can be reduced by a single warp using cooperative-group collectives directly in registers. Finally, we also transpose the weight matrix during initialization such that M rows for each column are contiguous in memory. We fuse the operations inside a transformer layer at four main regions: 1) the QKV GeMM and input layer-norm, 2) transposition plus attention, 3) postattention layer-norm and intermediate GeMM, and 4) bias and residual addition.

2022 DyLoRA: Parameter Efficient Tuning of Pre-trained Models using Dynamic Search-Free Low-Rank Adaptation

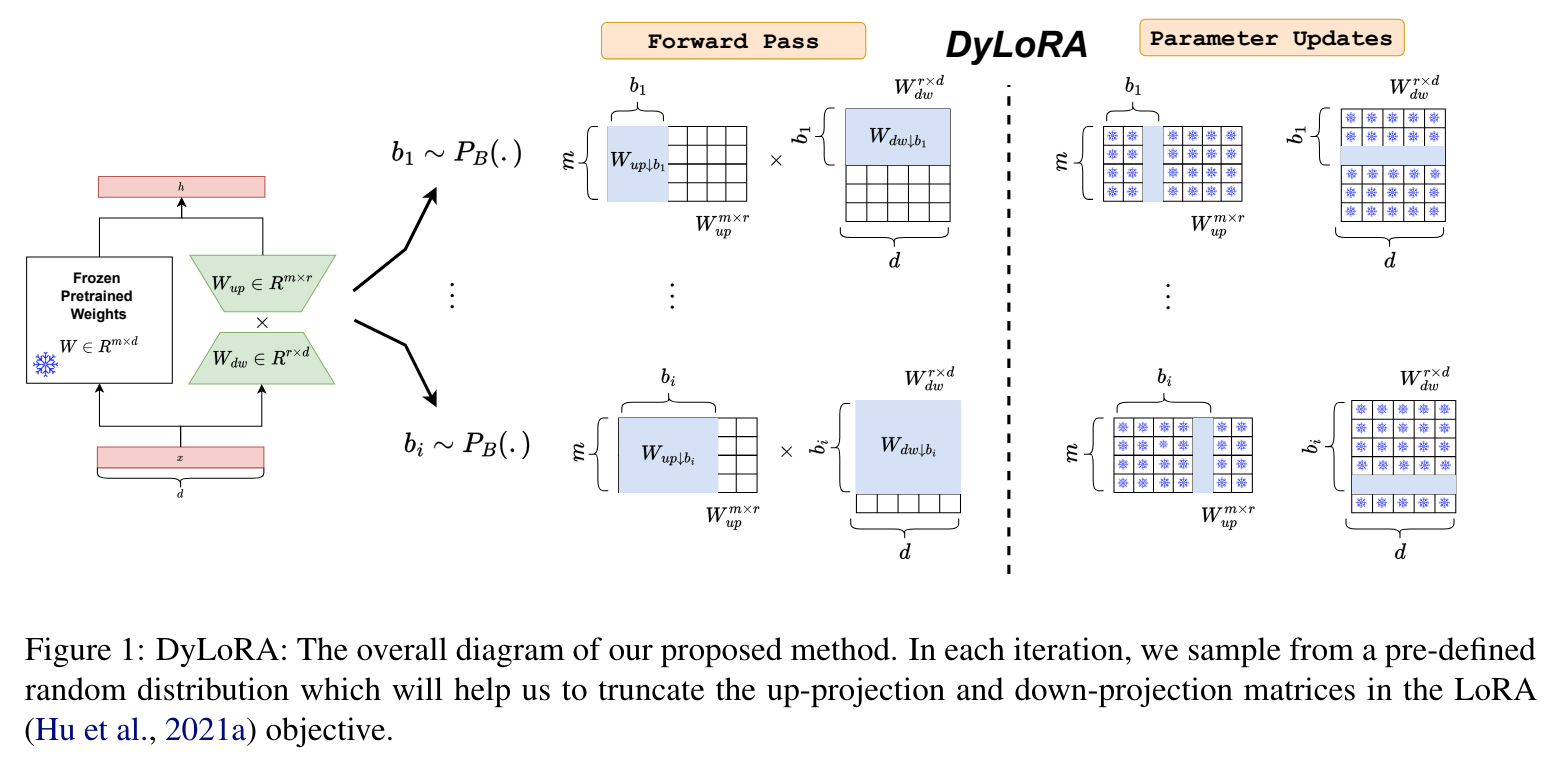

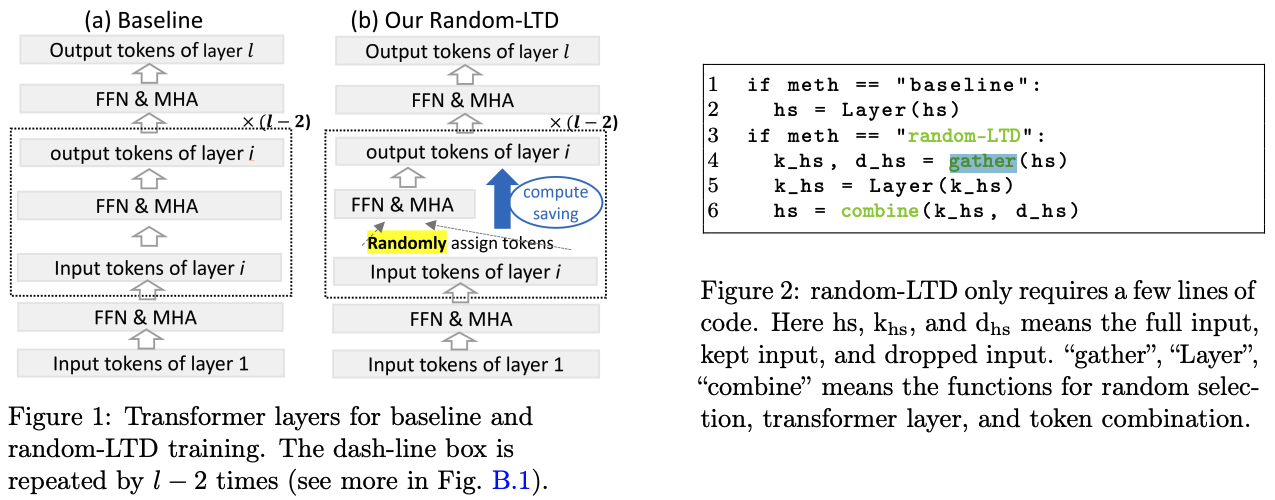

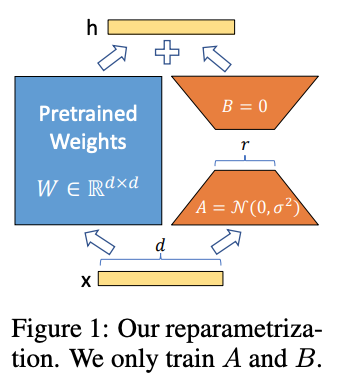

LoRA blocks “suffer from two major problems: first, the size of these blocks is fixed and cannot be modified after training (for example, if we need to change the rank of LoRA blocks, then we need to re-train them from scratch); second, optimizing their rank requires an exhaustive search and effort”. Dynamic LoRA (DyLoRA) addresses these two problems. “DyLoRA method trains LoRA blocks for a range of ranks instead of a single rank by sorting the representation learned by the adapter module at different ranks during training”. How does it work:

- In each LoRA module, we have an up-projection (\(W_{up} ∈ R^{m×r}\)) and a down-projection matrix (\(W_{dw} ∈ R^{r×d}\)). Let’s assume that we would like to train the LoRA module to operate in the range of \(r ∈\) Range \([r_{min}, r_{max}]\) where \(r_{min}\) and \(r_{max}\) are hyper-parameters.

- At each training step, we sample \(b\) (a value between ranks \(r_{min}\) and \(r_{max}\)), and truncate \(W_{dw}\) and \(W_{up}\) to include only \(b\) columns/rows, accordingly. The truncated matrices are represented as \(W_{dw↓b}\) and \(W_{up↓b}\), and they’re the ones used in this training step: \(h = W_0x + \frac{α}{b} W_{up↓b} W_{dw↓b} x\).

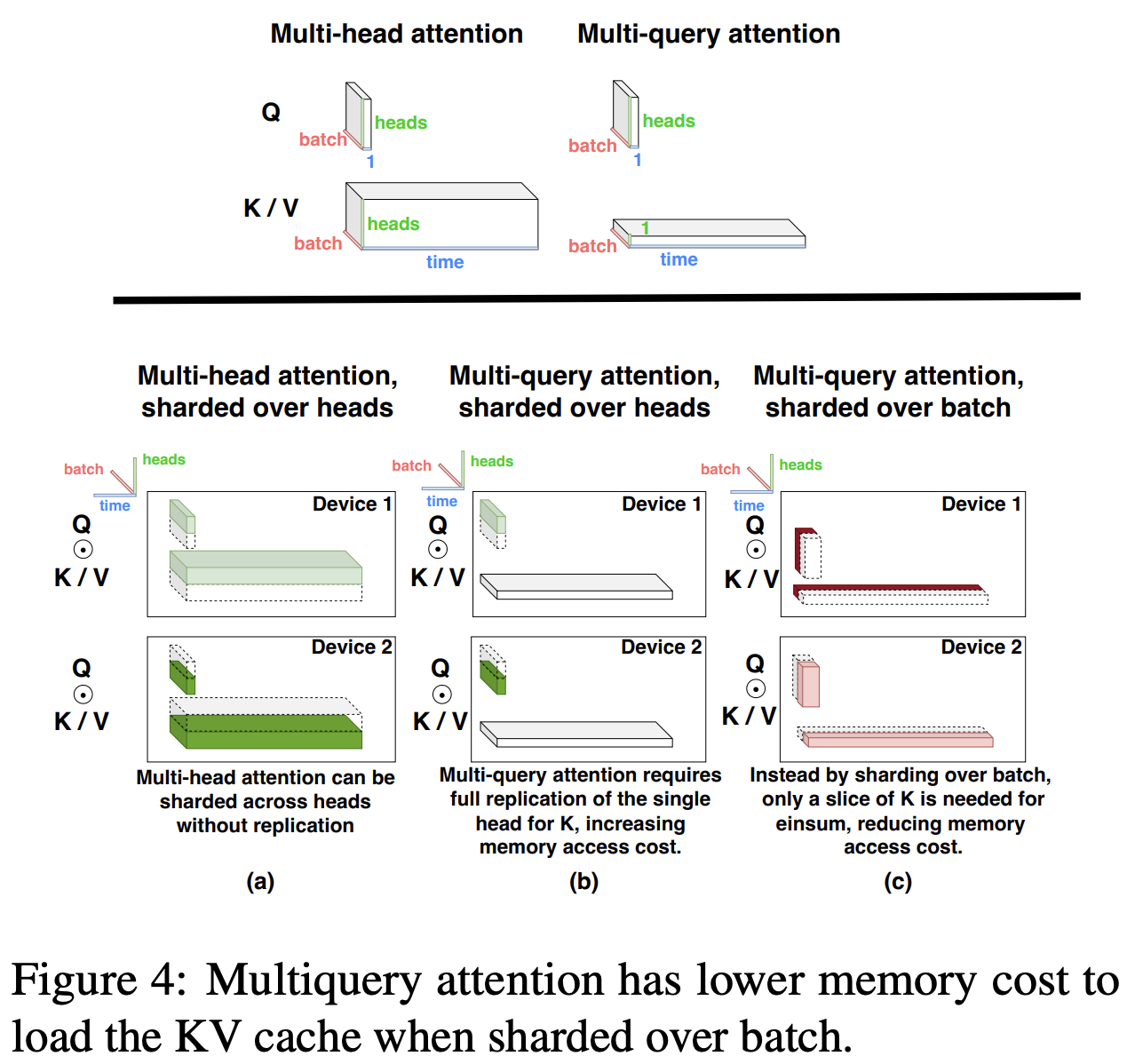

2022 Efficiently Scaling Transformer Inference, Google

The paper focuses on efficient generative inference of Transformer models with large deep models, with tight latency targets and long sequence lengths. It claims its methods surpass the efficiency of NVIDIA’s FasterTransformer. It is highly foccused on 3D-torus network layouts.

Section 3.1 provides an analysis of collective communication. Section 3.2 analyzes parallelism in the FeedForward module. Notation used: \(BLE_{xyz}\) means that the last dimension \(E\) of a tensor of logical shape \(BLE\) is split into \(X × Y × Z\), ie the per-chip tensor is of shape \([B, L, E/(X × Y × Z)]\) (omitted axis are replicated). \(F\) is the input size of the feed forward layer. It compares data splitting a la Megatron (1D weight-stationaly layout, section 3.2.1) where the partition layout for weights is \(EF_{xyz}\) and \(F_{xyz}E\), i.e. partitioned in to \(X × Y × Z = n_{chips}\); with a 2D weight-stationary layout along both the E and F axes (section 3.2.2), where shards are square, compute cost is the same but communication is more efficient and scalable (particularly on more than 16 chips). Section 2.3.3 describes the XYZweight-gathered approach, where “the output of each per-chip matrix multiplication must then be aggregated between chips to be used as input to the subsequent operations”, however “for very large batch sizes, it is best to keep the activations fully stationary between sequential matrix multiplications, requiring that we fully transfer the weights between all chips”.