Distributed Sorting Algorithms

Sorting is probably the most common computer science algorithm. In practice, at some point in life, every CS student studied the computational complexity of sorting algorithms, as measured by the Big-O notation. Sorting of serial algorithms on a single compute node is a solved problem, with dozens of algorithms already available. To name a few:

- quicksort: probably the most famous of all, relies on comparing a pivot term and to the remainder elements of the list recursively. Performance ranges from \(O (n^2) for the worst-case scenario (already sorted input) to\)n log (n) $$;

- insertion sort: iteratively takes one element from a list and inserts it into a final list of sorted elements. Efficient for small datasets, with an efficient ranging from \(O (n^2)\) to \(O (n)\) if elements to be inserted are found immediately in the final list;

- selection list: a swapping algorithm that iteratively finds the smallest element in an unsorted list, and swaps it with the leftmost unsorted, decreasing the unsorted list size by 1. It is computationally inefficient as it requires \(O(n^2)\) comparisons, yet memory efficient with \(O(n)\) memory swaps;

- merge sort: probably the most general-purpose sorting algorithm. Created by John Von Neumann, follows a divide-and-conquer algorithm that divides a list into \(n\) sublists that recursively merge larger lists until the initial set is sorted. Best and worst case scenario run with complexity \(O (n log n)\);

- heap sort: similar to the selection sort mentioned previously, yet improved as it uses a heap data structure rather than a linear-time search to find the elements in the unsorted list, leading to a complexity of \(O(n log n)\) (with \(O(n)\) complexity in the extreme case of having all elements on the list being equal);

- bubble sort: performs sequential swaps of neighboring elements until sorting is completed. Thus requires an halved all-to-all number of operations, leading to a complexity of \(O(n^2)\). The best case scenario complexity is \(O(n)\) and is possible only if elements are sorted beforehand;

- counting sort: highly efficient for integer values distributed across a small range of values. Navigates the list of unsorted elements once and increments the value counts on an array of counts (initialized as zero and of the same size as the value range). \(O(n+k)\) efficiency for navigating initial list of size \(n\) and count array of range \(k\);

- radix_sort: an adaptation of the previous to larger intervals, by sequentially ordering integer values by their key (given by the digit in a given positiion in the number). Iterations start from the smallest to largest digit, and perform a counting sort (per i-th digit as key) at every iteration. Complexity: \(O(d(n+k))\) where \(d\) is the number of iterations given by the number of integer places (e.g. \(d=3\) for value \(991\)).

- bucket sort: efficient on multicore architectures. Distributes a set o \(n\) values into \(b\) buckets, then sorts each bucket independently. The next operation keeps a pointer on every bucket and iteratively picks the smallest elements across all buckets. The picked elements are now sorted. Complexity \(O(n)\) for iterating through inital dataset in the first scatter phase, plus the complexity of sorting \(n/b\) elements on each bucket, plus final iteration to merge sorted buckets in the gather phase (\(O(n)\)).

- and others…

Most of these algorithms allow for a multicore implementation and the underlying recursive- or tree-based nature of the problem and are well suitable for a parallel execution on a single memory region.

However, if the list of elements is spread across a network of compute nodes — i.e. a distributed memory environment — the resolution is not trivial. With that in mind, we present two algorithms for the sorting of distributed lists.

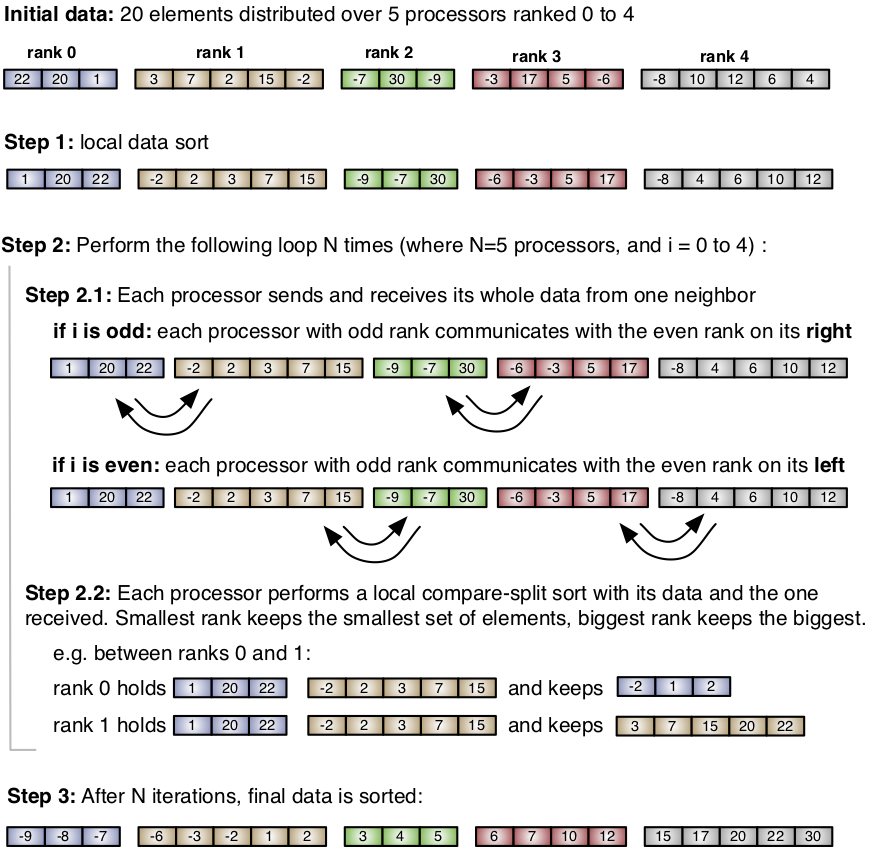

The first one is the Odd-Even sort, a distributed swap based sort algorithm. Its rationale is the following:

- compute nodes (ranks) are numbered iteratively. Each node has two neighbors that refer to the next and previous rank;

- at every iteration, every node sorts its elements, and sends the first half to a neighbor and the second half to the other neighbor;

- when a number of iterations equal to the number of compute nodes have been executed, the operation is completed.

The algorithm is illustrated with a sample dataset in the following workflow:

The algorithm has the advantage of being very memory-stable i.e. one can predict in advance the worst-case scenario in terms of memory consumption. Moreover, each compute node holds the same number of elements it started with, therefore load balancing is guaranteed across nodes. However, for a very large network of nodes, it is inefficient as it requires a high number of iterations.

A faster alternative is based on a distributed implementation of the sample sort. The algorithm is as follows:

- Each compute node sorts their local dataset and collects some samples from few equidistant values on the dataset;

- Samples are sent to the master rank, who will sort them and collect \(c\) equidistant samples (for \(c\) compute nodes) from the set of received samples;

- The master rank broadcasts the new samples to the network. Each sample pair delimits the range/interval of values to be sent to each node;

- Based on those ranges, the network of compute nodes perform a collective scatter-gather (or a selective all-to-all) where they send each element to the appropiate target rank;

- A final sorting of the data at each memory region will yield a globaly distributed dataset on the network.

Here is an illustrative workflow:

This method is computationally very efficient as the number of communication operations is constant, independently of the input size of network size. However, it may lead to a highly heterogeneous number of elements across number nodes. This leads to a computational and memory imbalance. If necessary, a network balance operation may follow the sorting in order to balance the dataset across the network. This balancing operation and the sorting of spatial datasets are covered in a different post.

The C++ implementation of both algorithms is available in DistributedMemorySorter.cxx and DistributedMemorySorter.h.