Building a GPT model in C++, and benchmarking LibTorch, PyTorch, TorchScript and torch.compile

In the recent Pytorch 2.x release announcement, the Torch developers decided to move that structure of PyTorch from a python interface of a C++ core (highly efficient) to a Python-based implementation that calls a small set of c++ kernels (developer friendly). They also announced torch.compile as a method to perform a JIT compilation and optimization of the execution graph that tremendously speeds up the execution.

So the main questions are: how much faster are the C++ model implementations compared to a Python one? If Python is the de facto corelanguage for training, can we perform inference efficiently on a compiled C++ code? How good is torch.compile really?

Change of philosophy: from Python to C++ to Python

Initial releases of pytorch were mostly written in python. Until the release of Python 2.x, the belief was that “to keep eager execution at high-performance, we’ve had to move substantial parts of PyTorch internals into C++”. In practice, python has the overhead of the runtime itself, dynamic typing, JIT, interpreted code, etc. So moving PyTorch API to C++ and using python as a thin layer that calls the C++ compiled implementations seemed logical.

Now, with PyTorch 2.x, they’re moving in the complete opposite direction, claiming that the “philosophy on PyTorch has always been to keep flexibility and hackability our top priority, and performance as a close second” and “moving internals into C++ makes them less hackable and increases the barrier of entry for code contributions”. So in practice, the library of 2000+ operations written in C++ is being reduced and the “goal is to provide a primitive and stable set of ~250 [C++] operators with simplified semantics, called PrimTorch”.

In brief, in order to favour PyTorch contributors that prefered Python over C++, they are limiting the C++ code to a few hundred kernels, and will have all the remaining code implemented in python only. Hardware vendors can then focus on their specific implementation of that subset of C++ methods, while the python runtime will execute the higher level operations. Sounds good, but the possibility of training a model using only C++ in the next releases of PyTorch remains uncertain.

Kernel optimization via torch.compile

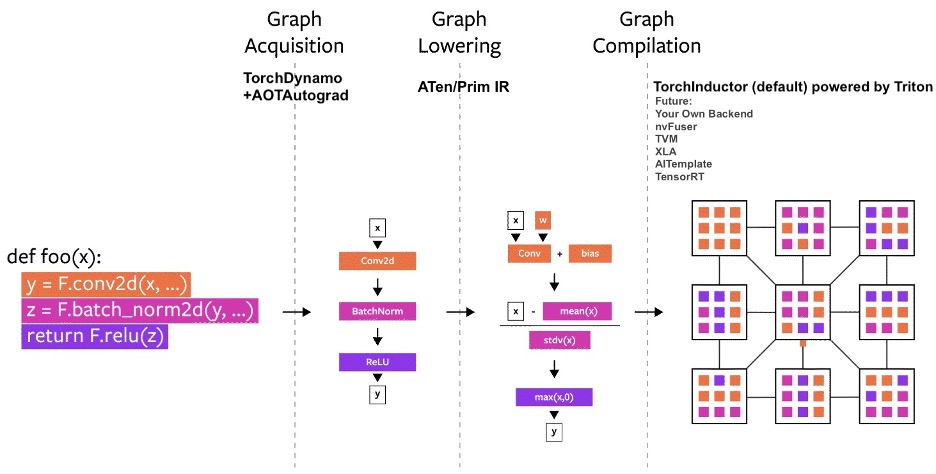

The other big announcement was torch.compile, that “makes PyTorch code run faster by JIT-compiling PyTorch code into optimized kernels, all while requiring minimal code changes”. The torch compile algorithm runs three steps:

- graph acquisition will build the execution graph of all PyTorch operations. Nodes that can be combined and optimized together will be merged, and subsequently, graph will be rewritten as a graph of subgraphs. Parallel (graph leaves) and sequential modules are now exposed.

- graph lowering will decompose the previous operations into kernels that are native to the specific backend.

- graph compilation will convert the kernels into low-level operations that are specific to the device.

A diagram of the three steps of torch.compile. Source: PyTorch 2.0 technology overview

Kernel fusion is complex, so there are two settings worth the mention. The option mode selects the tradeoff between runtime and memory in the generated graph (from the docs and API):

defaultoptimizes for large models, with low compile-time and no extra memory overhead. It is “a good balance between performance and overhead”;reduce-overheadreduces the overhead of python with CUDA graphs, it is faster than the previous model but uses some extra memory. It helps speed up small models. CUDA graphs allows an execution graph of kernels to be defined beforehand and launched only once from CPU, instead of having kernels launched individually;max-autotuneleverages Triton based matrix multiplications and convolutions It enables CUDA graphs by default. It produces the fastest model, but takes a very long time to compile.max-autotune-no-cudagraphsis analogous, but without the CUDA graphs.

The flag fullgraph specifies whether the compilation outputs a single graph for the whole run, or it can be broken into several partial graphs (that can be reutilized across the main graph), and is only relevant for users that need to squeeze the very best performance. This is in practice similar to the inline logic in the C programming language. These two settings are specified by, and defaulted to torch.compile(model, mode='default', fullgraph=False).

About this post

In this post, we will benchmark and analyse several implementations of ML training and inference performed on different backends: PyTorch 1.3.1 (python), PyTorch 2.1.2 (python), LibTorch 2.1.2 (C++), TorchScript 2.1.2 (python and C++), and PyTorch 2.1.2 with torch.compile (python).

We will look at two different testbenches, so feel free to pick one based on your level of expertise and interest:

- the small variant of the GPT2 model, introduced in Building a GPT model from scratch, will be detailed in section GPTlite on LibTorch C++. This is a complex example that is specific to the use case of large language models;

- a Deep Neural Network of arbitrary width and depth, in section Benchmark Model on LibTorch C++. This is a very simple example that will be used to benchmark our metrics on models of varying depths and widths. It is mostly suitable for those who are interested in performance modeling, ML engineering, and the C++/Python/TorchScript comparison.

In this post, we will detail and benchmark the C++ implementation of a small variant of the GPT2 model with N decoder blocks (left), and of a simple Deep Neural Network with L layers of dimensionality W (right). Then we will benchmark their C++, PyTorch, TorchScript and torch.compile implementations.

GPTlite on LibTorch C++

We will start with the GPT implementation in C++. The subsections that follow match exactly the structure of the post with the GPTlite implementation in Python.

Hyperparameters

Our GPTlite will be written in the header-only format in the file gptlite.h. We start with the hyperparameter declarations:

#pragma once

#include <torch/torch.h>

// replicate GPT-2 Small, Table 2.1, "Language Models are Few-Shot Learners, Brown 2021)"

// depth of the network as number of decoder blocks.

const int n_layer = 12;

// size of the embeddings (d_model)

const int n_embd = 768;

// number of attention heads in the Multi-Attention mechanism

const int n_head = 12;

// block size ie max number of training sequence, the $n_{ctx}$ in the paper .

const int block_size = 2048;

// dropout rate (variable p) for dropout units, renamed to avoid ambiguity

const float dropout_p = 0.1;

// namespace and data type aliases

namespace nn = torch::nn;

using Tensor = torch::Tensor;

Multi-Head Masked Attention

Remember the original formulation of the multi-head shared attention heads, where \(W^Q\), \(W^K\) and \(W^V\) are matrices / projections / linear layers:

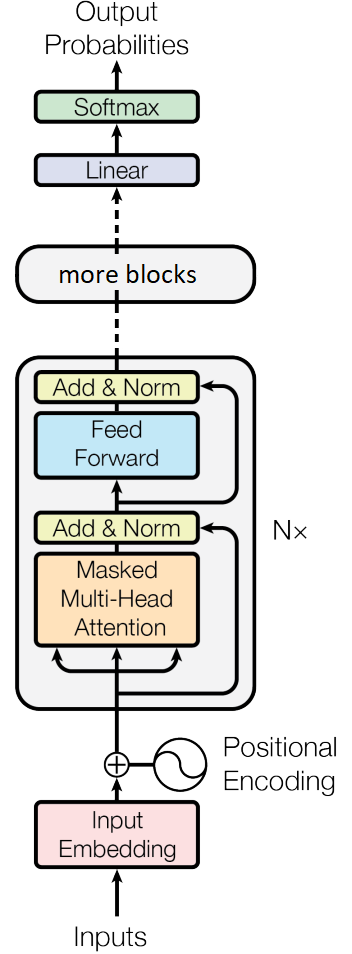

\[MultiHead(Q, K, V ) = Concat(head_1, ..., head_h)W^O\] \[\text{where } head_i = Attention(QW^Q_i, KW^K_i, VW^V_i)\] \[\text{where } Attention(Q,K,V) = softmax \left( \frac{QK^T}{\sqrt{d_k}} \right) \, V\]Together with the upper-diagonal mask, this is the underlying structure of each of the N attention blocks in the model:

The multi-head (Nx) attention module in the GPTlite model, emphasized in red.

The C++ code is analogous to the python implementation. We start by defining a single attention head:

struct Head : nn::Module {

Head(int head_size) {

int head_size = head_size;

nn::Linear key = nn::Linear( nn::LinearOptions(n_embd, head_size).bias(false) );

nn::Linear query = nn::Linear( nn::LinearOptions(n_embd, head_size).bias(false) );

nn::Linear value = nn::Linear( nn::LinearOptions(n_embd, head_size).bias(false) );

Tensor tril = torch::tril(torch::ones( {block_size, block_size} ));

nn::Dropout dropout = nn::Dropout(dropout_p);

register_module("key", key);

register_module("query", query);

register_module("value", value);

register_buffer("tril", tril);

register_module("dropout", this->dropout);

}

Tensor forward(Tensor x){

int B=x.size(0), T=x.size(1), C=x.size(2);

Tensor k = key(x); //shape (B,T, head_size)

Tensor q = query(x); //shape (B,T, head_size)

Tensor v = value(x); //shape (B,T, head_size)

// compute self-attention scores

Tensor wei = torch::matmul(q, k.transpose(-2, -1)); //shape (B,T, T)

wei = wei * std::pow(C,-0.5); //scale by sqrt(d_k)

wei = wei.masked_fill(tril.slice(0, 0, T).slice(1, 0, T) == 0, -inf);

wei = F::softmax(wei, -1); // (B, T, T)

wei = this->dropout(wei);

// perform weighted aggregation of values

Tensor out = torch::matmul(wei, v); // shape (B, T, head_size)

return out;

}

}

In order to keep the code small and clean, Head and all our modules that follow will be defined as a struct and not as a class, so that all members are public and not private by default.

Note the register_module operator that is not needed in the python implementation. Why do we need this? In practice, C++ has no reflection, so it cannot iterate over a class variables, unless they’re declared somewhere. However, we need this iterator feature, so that LibTorch can iterate class members for e.g. parameter count, recursive copy of submodules to a device, back propagation of weights among several heads, etc. There are two options to create this iterator, and in this post we will use both:

- We can keep all modules inside an LibTorch container such

nn::Sequentialornn::ModuleList. Applying a function to the container will recursively apply it to every module inside; - We can call

register_parameter,register_bufferandregister_moduleto register parameters, buffers or modules during initialization, and LibTorch will keep track of these internally.

Also, in the code above, we do register_buffer on tril because it is a tensor that is not a parameter, but a state, i.e. torch will not record its gradients.

Finally, LibTorch does not allow named arguments like in Python e.g. bias=False, so these cannot be passed directly. The possible constructors are Linear(in_features, out_features) or Linear(LinearOptions(in_features, out_features).bias(False)), so when we need to pass any named parameters, we use the second constructor and wrap all options inside LinearOptions.

We will now combine (concatenate) the output of all heads into our multi-head shared-attention module:

struct MultiHeadAttention : nn::Module {

MultiHeadAttention(int num_heads, int head_size) {

nn::ModuleList heads = torch::nn::ModuleList();

for (int i=0; i<num_heads; i++)

heads->push_back( Head(head_size) );

nn::Linear proj = nn::Linear(num_heads*head_size, n_embd);

nn::Dropout dropout = nn::Dropout(dropout_p);

register_module("heads", heads);

register_module("proj", proj);

register_module("dropout", this->dropout);

}

Tensor forward(Tensor x){

//Concatenate the outputs of the heads along the last dimension

Tensor outputs[n_head];

for (int i=0; i<n_head; i++){

Head* head = heads[i]->as<Head>();

outputs[i] = head->forward(x);

}

Tensor out = torch::cat(outputs, -1);

out = proj(out);

out = this->dropout(out);

return out;

}

}

Again, we used nn::ModuleList as a container, instead of any std-library container. Containers in C++ are declared for a given fixed element type. So, the tricky bit here is that nn::ModuleList stores elements of type nn::Module that needs to be casted dynamically to its base type Head with module->as<Head>() before calling the internal members of the instantiated Head.

Feed Forward Network

The Feed-forward network is a two-layer Deep Neural Network and is pretty straighforward to implement:

The feed forward network in the GPTlite model, emphasized in red.

struct FeedForward : nn::Module {

FeedForward(int n_embd) {

nn::Sequential net = nn::Sequential(

nn::Linear(n_embd, n_embd*4),

nn::ReLU(),

nn::Linear(n_embd*4, n_embd),

nn::Dropout(dropout_p)

);

register_module("net", net);

Tensor forward(Tensor x) {

return net->forward(x);

}

}

The GPT Block

We’ll call GPT block the sequence of a multi-head attention and a feedforward module. Similarly to the python implementation, we add skip connections and normalization before the attention and feed-forward network.

The GPT block(s) in the GPTlite model, emphasized in red.

struct Block : nn::Module {

Block(int n_embd, int n_head) {

int head_size = (int) (n_embd / n_head);

std::shared_ptr<MultiHeadAttention> sa =

std::shared_ptr<MultiHeadAttention>( new MultiHeadAttention(n_head, head_size) );

std::shared_ptr<FeedForward> ffwd =

std::shared_ptr<FeedForward>( new FeedForward(n_embd) );

nn::LayerNorm ln1 = nn::LayerNorm( std::vector<int64_t> {n_embd} );

nn::LayerNorm ln2 = nn::LayerNorm( std::vector<int64_t> {n_embd} );

register_module("sa", sa);

register_module("ffwd", ffwd);

register_module("ln1", ln1);

register_module("ln2", ln2);

}

Tensor forward(Tensor x) {

x = x + sa->forward(ln1(x));

x = x + ffwd->forward(ln2(x));

return x;

}

}

You will notice we will be using shared_ptr to wrap our classes. It is not accidental. In fact, all LibTorch modules are a shared pointer to the implementation of a given class. Thus, all torch::nn modules can be passed by value directly. E.g. the linear layer nn::Linear is just an alias for std::shared_ptr<nn::LinearImpl>, where nn::LinearImpl is the implementation. Because of this, the documentation suggests initializing modules with nullptr as the default value of the pointer, and initializing the implementation dynamically later when needed. This is because the alternative of not initializing the pointer would call the default constructor e.g. Linear() which is not defined, and lead to a compilation error.

There’s also a subtle difference in the LayerNorm initialization. By design, LayerNorm accepts a list of normalized dimensions as input. Alternatively, in the python implementation, when a single int value is passed, only the last dimension of the input is normalized, and will be resized to the integer value. However, in C++, LayerNorm does not include the constructor initialization with a single integer argument, so we have to use the general constructor and pass it as a singleton list.

Final GPTlite Model

Putting it all together:

struct GPTlite : nn::Module {

GPTlite(int vocab_size){

nn::Embedding token_embedding_table = nn::Embedding(vocab_size, n_embd);

nn::Embedding position_embedding_table = nn::Embedding(block_size, n_embd);

nn::Sequential blocks = nn::Sequential();

for (int i=0; i<n_layer; i++)

blocks->push_back( Block(n_embd, n_head) );

nn::LayerNorm ln = nn::LayerNorm( std::vector<int64_t> {n_embd} );

nn::Linear lm_head = nn::Linear( nn::LinearOptions(n_embd, vocab_size).bias(false) );

register_module("token_embedding_table", token_embedding_table);

register_module("position_embedding_table", position_embedding_table);

register_module("blocks", blocks);

register_module("ln", ln);

register_module("lm_head", lm_head);

}

Tensor forward(Tensor idx){

int T = idx.size(1);

Tensor tok_emb = token_embedding_table(idx); //shape (B,T,C)

Tensor pos_emb = position_embedding_table(torch::arange(T).to( idx.device() )); // (T,C)

Tensor x = tok_emb + pos_emb; //shape (B,T,C)

x = blocks->forward(x);

x = ln(x);

Tensor logits = lm_head(x); //shape (B,T,C)

return logits.permute({0,2,1}); //shape (B,C,T)

}

}

Benchmark Model on LibTorch C++

We will define a simple benchmark model, which is simply a DNN with L layers of width W, with a ReLu activation between layers. This is defined in benchmark.h as:

#pragma once

#include <torch/torch.h>

struct BenchmarkModel : torch::nn::Module {

/// DNN with L layers and W neurons per layer

BenchmarkModel(int64_t W, int64_t L, int64_t in_size, int64_t out_size){

torch::nn::Sequential layers = torch::nn::Sequential();

layers->push_back(torch::nn::Linear(in_size, W));

layers->push_back(torch::nn::ReLU());

for (int64_t l = 0; l<L-2; ++l) {

layers->push_back(torch::nn::Linear(W, W));

layers->push_back(torch::nn::ReLU());

}

layers->push_back(torch::nn::Linear(W, out_size));

layers->push_back(torch::nn::ReLU());

register_module("layers", layers);

this->to(device);

}

torch::Tensor forward(torch::Tensor input) {

return layers->forward(input);

}

}

Main loop

Our main.cpp file will contain a loop that will benchmark the train and inference operations of a model for a random input:

#include "gptlite.h"

#include "benchmark.h"

torch::Device device = torch::cuda::is_available() ? torch::kCUDA : torch::kCPU;

int main(int argc, const char* argv[]) {

const int vocab_size = 65, batch_size=1;

const torch::ScalarType Long = torch::ScalarType::Long;

torch::Tensor idx = torch::randint(0, vocab_size, {batch_size, block_size}, device).to(Long);

torch::Tensor label = torch::randint(0, vocab_size, {batch_size, block_size}, device).to(Long);

GPTlite model = GPTlite(vocab_size);

model.to(device);

benchmark_train<GPTlite>(model, idx, label);

benchmark_inference<GPTlite>(model, idx);

}

As an important remark, LibTorch does not include a C++ equivalent to torch.set_default_device, so we have to manually move to the GPU every datapoint and module. And because we registered every parameter, buffer and module previously, doing model.to(device) will recursively copy all the contents in the model to the device. The final functions benchmark_train and benchmark_inference perform the benchmark of method several train and inference epochs, respectively. The C++ implementation is analogous to its python counterpart, however we’ll use a templated typename ModelType to cover all possible model implementations:

const uint warmup_epochs = 30; // number of epochs to run before benchmarking

const uint benchmark_epochs = 30; // number of epochs to benchmark

template <typename ModelType>

void benchmark_train(ModelType & model, torch::Tensor x, torch::Tensor label) {

clock_t start_time;

torch::Tensor output, loss;

model.train();

torch::optim::Adam optimizer( model.parameters(),

torch::optim::AdamOptions(2e-4).betas(std::make_tuple(0.5, 0.5)));

for (int64_t epoch = 0; epoch < warmup_epochs + benchmark_epochs; ++epoch) {

if (epoch == warmup_epochs)

start_time = clock();

optimizer.zero_grad();

output = model.forward(x);

output = F::softmax(output, F::SoftmaxFuncOptions(1));

loss = torch::cross_entropy_loss(output, label);

loss.backward();

optimizer.step();

}

double benchmark_time = double(clock() - start_time) / CLOCKS_PER_SEC;

double throughput = benchmark_epochs / benchmark_time;

std::cout << "train runtime: " << benchmark_time << " seconds" << std::endl;

std::cout << "train throughput: " << throughput << " epochs/second" << std::endl;

}

The implementation of benchmark_inference is a much simpler loop with model.eval() instead, the torch::NoGradGuard variable (equivalent to with torch.no_grad() in python), and only a forward pass in the epochs loop. However, we add an extra templated type for the input data, to support the TorchScript-based inference that we will discuss in the next chapter:

template <typename ModelType, typename InputType = torch::Tensor>

void benchmark_inference(ModelType & model, InputType x) {

clock_t start_time;

model.eval();

{

//no_grad scope, C++ equivalent to 'with torch.no_grad()' in Python

torch::NoGradGuard no_grad;

for (int64_t epoch = 0; epoch < warmup_epochs; ++epoch)

model.forward(x);

start_time = clock();

for (int64_t epoch = 0; epoch < benchmark_epochs; ++epoch)

model.forward(x);

}

double benchmark_time = double(clock() - start_time) / CLOCKS_PER_SEC;

double throughput = benchmark_epochs / benchmark_time;

std::cout << "inference runtime: " << benchmark_time << " seconds" << std::endl;

std::cout << "inference throughput: " << throughput << " epochs/second" << std::endl;

}

TorchScript: python for training, C++ for inference

In ideal scenarions, we would want the flexibility and speed of development of python, with the low memory footprint and high efficiency of C++. This is possible with TorchScript. To do that, we will train the model model in python and output it as the binary model_jit.pt file, via:

model_jit = torch.jit.script(model)

# model_jit = torch.jit.trace(model, (x))

model_jit.save('model_jit.pt')

The main difference between script and trace is that scripting computes the execution graph by looking at the the model definition (nn.Module) while tracing does a forward pass and freezes that execution graph to compute it. Thus, tracing ienforces a deterministic execution (no control flows allowed) and is limited to PyTorch tensors and PyTorch operations in the forward pass. In case of doubte, favor scripting for portability, and tracing for performance.

Important: you cannot use torch.jit.save on a model optimized with torch.compite, or you’ll get the error Compiled functions can't take variable number of arguments or use keyword-only arguments with defaults. You have to use instead torch.jit.trace(model, (x)) .

On the inference side, in C++, we follow the LibTorch documentation and will load and run inference on that model with the following code:

#include <torch/script.h>

using JitModule = torch::jit::Module;

using JitInput = std::vector<torch::jit::IValue>;

JitModule model = torch::jit::load("model_jit.pt").to(device);

benchmark_inference<JitModule, JitInput>(model, {x});

Note that the type of the model and input data is not torch::nn::Module and torch::Tensor as before. Instead, we have torch::jit::Module and std::vector<torch::jit::IValue>, respectively. This justifies the use of the templates on the definition of benchmark_interface.

Compilation

We follow the instructions on the LibTorch documentation and use the CMake build systems to generate our binaries. The CMakeLists.txt is:

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.18 FATAL_ERROR)

project(torch_cpp_benchmark)

# Fix error "CMAKE_CUDA_ARCHITECTURES must be non-empty if set."

set(CMAKE_CUDA_ARCHITECTURES "native")

find_package(Torch REQUIRED)

set(CMAKE_CXX_FLAGS "${CMAKE_CXX_FLAGS} ${TORCH_CXX_FLAGS}")

set(SOURCE_FILES gptlite.h benchmark.h main.cpp)

add_executable(main ${SOURCE_FILES} )

target_link_libraries(main "${TORCH_LIBRARIES}")

set_property(TARGET main PROPERTY CXX_STANDARD 17)

and we will run cmake in Release mode (for compile optimizations), and we specify the path of LibTorch, and (optionally) two extra flags to compile our code with the cuDNN and cuSPARSELt libraries:

cmake .. \

-DCMAKE_BUILD_TYPE=Release \

-DCAFFE2_USE_CUDNN=1 -DCAFFE2_USE_CUSPARSELT=1 \

-DCMAKE_PREFIX_PATH=`python3 -c 'import torch;print(torch.utils.cmake_prefix_path)'`

Benchmark

We compared the throughput (samples/sec) and GPU memory usage (GBs) of three distinct implementations:

- the small variant of GPTlite;

- a deep benchmark model made of 2048 layers with 256 activations per layer, with input and output of size 2048; and

- a wide benchmark model of 3 layers with 8192 activations each, with input and output of size 2048.

So in practice we are testing a very deep DNN, a very shallow DNN and a large language model. For each model, we tested:

- the python PyTorch implementation of training and inference on versions 1.3.1 and 2.1.2;

- the C++ LibTorch 2.1.2 implementation of train and inference; and

- the TorchScript combo, using PyTorch 2.1.2 to train and output the model, and C++ LibTorch 2.1.2 to load and perform inference.

- the train and inference using

torch.compileon Python 2.1.2;

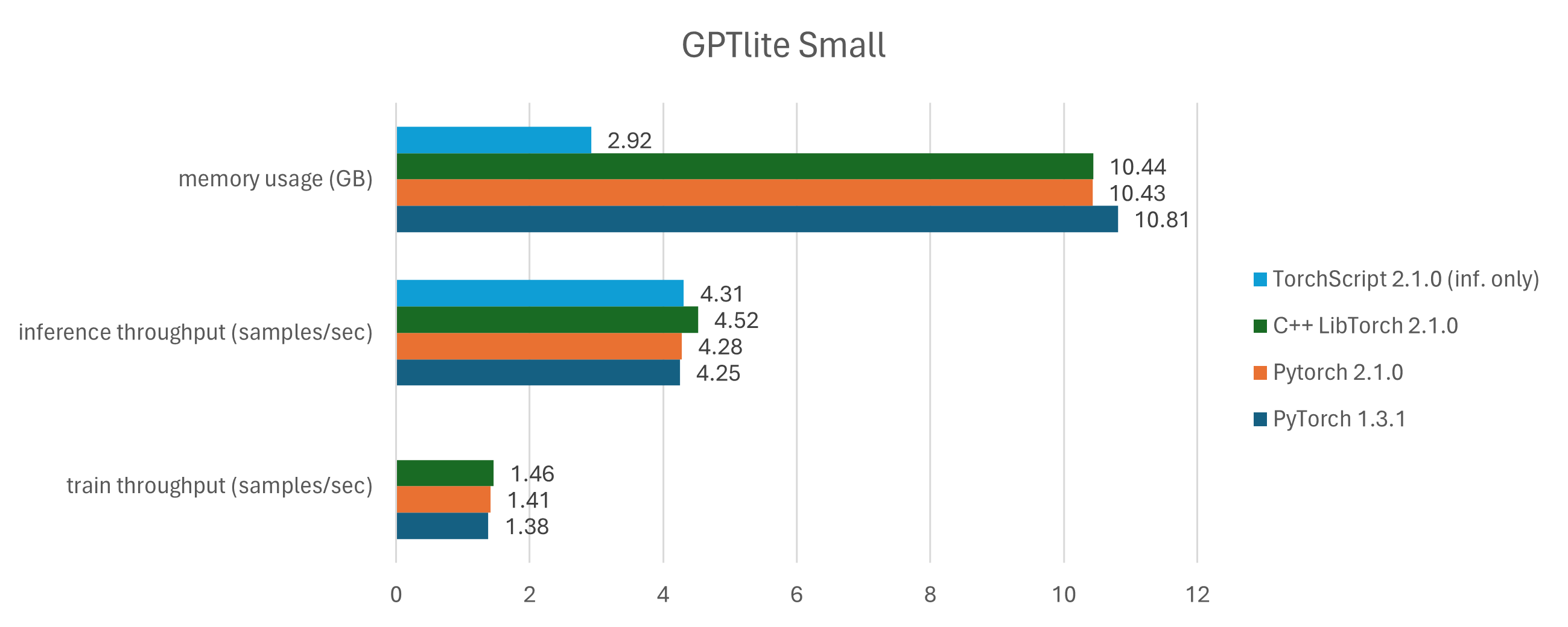

As an important remark, I noticed that both the python and C++ implementations of Torch leak memory on the GPU when several models are allocated in the same run, as the deallocation does not clear the memory completely. For that reason, I executed a new run per benchmark value. The results for the GPTlite modeo are the following:

The benchmark for the bencmark models are in benchmark_wide.png and benchmark_deep.png. Looking at the GPU memory usage, we see that there is a much smaller memory requirement for inference-only runs (light blue bars), compared to runs that performed train and inference (navy blue, orange, and green bars). This is expected, due to the extra parameters and optimizer values required for training. Training leads to an increase in memory in the order of 4x to 10x.

Looking at the overall performance, there is a gain of up to 15% in throughput when moving from PyTorch 1.3.1 to 2.1.2 (navy blue to orange bars). Also, there is also a small throughput increase of up to 10% when moving from PyTorch 2.1.2 to its C++ LibTorch equivalent (from orange to green bars), explained by the python overhead (runtime, dynamic typing, etc). Finally, the inference when comparing the pure C++ implementation and the TorchScript implementation (train in python, inference in C++) is neglegible, which means that TorchScript does a pretty good job in (de)serializing the model.

We also tested the speed-up gains from using torch.compile on our GPT-lite model. The base case without torch.compile performs the PyTorch-based training at a throughput of 1.41 samples/sec and inference at 4.28 samples/second. Let’s compare it with the same model compiled at different modes and with(out) a full graph:

| throughput (increase factor) | fullgraph=False train |

fullgraph=False, inference |

fullgraph=True, train |

fullgraph=True, inference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

mode='default' |

1.591 | 5.124 | 1.581 | 5.11 |

mode='reduce-overhead' |

1.625 | 5.256 | 1.624 | 5.258 |

mode='max-autotune' |

1.636 | 5.258 | 1.635 | 5.26 |

The final message is: running PyTorch 2.1 does not incur a massive loss of performance compared to LibTorch C++, and this justifies the move of the Torch team back to Python, to ease up development. Also, it is viable to perform training on PyTorch and inference on compiled LibTorch to fit light hardware setups that do not include the python runtime. However, torch.compile increases the training throughput by 12% to 16%, and the inference throughput by 19% to 23%, when compared to the Torch/LibTorch’s implementation, and this is the most efficient setup for most users. In terms of compilation settings, there was no major visible gain in using a full torch graph in the compilation, and reduce-overhead yielded the best balance between compilation time, memory and runtime.

Now the main questions are: is C++ LibTorch going to become deprecated and eventually disappear? If not, will torch.compile allow the export of compiled models with torch.jit.track / .script so that we can load and run it on LibTorch C++?

And we reached the end of this post! If you want to replicate these results, see the GPT-lite-cpp repo.